This article in the Washington Post is from a physician who specializes in palliative care. He’s advocating use of psychedelic drugs in the treatment of depression that often accompanies terminal illness.

I’m not sure how familiar he is with the realm of drug abuse, however. For instance, he casually remarks that psychedelics aren’t intoxicants because “they do not dull a person’s senses or induce sleepiness.” Well, neither does crystal meth. In fact, it does the opposite. But does that mean it isn’t an intoxicant?

Maybe he should meet some heavy speed users.

But his focus is on limited use with the terminally ill. It’s end of life stuff. Many therapies make sense in that context. He’s thinking of a medically supervised, carefully monitored, therapeutic episode based on a thorough assessment of a particular patient. In other words, a special need.

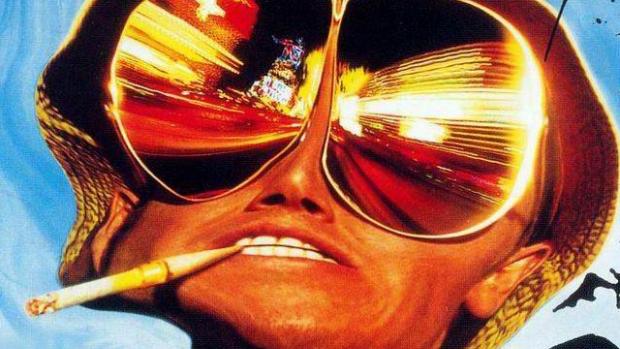

In any context, set and setting are probably as important as the substance itself. Those are Timothy Leary’s terms for the thoughts, beliefs, and emotions the patient brings to the experience (the set) and the physical and social environment where the episode occurs ( the setting). It’s likely the relative importance of substance, set, and setting vary from individual to individual and from episode to episode. It’s safe to conclude that set and setting are considered very important in a good outcome.

For example, a therapist might go to some lengths to orient the patient prior to the experience. That’s to reduce anxiety and foster a positive feeling about what is to come. Likewise, the physical environment would be deliberately calm and relaxing. Wouldn’t want any unexpected noises to send someone into a panic.

An additional concern: these same hallucinogens have a pronounced tendency to escape the research environment and find their way out into the streets (or into high schools or on college campuses, etc). They already have, haven’t they? They’re pretty much available everywhere, despite all the fearsome prohibitions. How’d that happen?

I was taught that hallucinogens aren’t classically addictive, because they don’t lend themselves to daily use. But that was when addiction was largely defined by tolerance and physical dependence. The cocaine epidemic changed all that. The emphasis switched to compulsion and continued use despite adverse consequences. Now that I’ve seen a fair amount of.

One 19 year old female would drop acid and stay up for days at a time playing video games. A psychotic break landed her in the hospital. She emerged from the psychosis a few weeks later. Some people don’t.

My point is, when you read articles on the great and good effects of psychedelic drugs, it’s easy for the uninitiated to come away thinking, aren’t these wonderful? No more suicide, no more ODs! I should probably take some, and I’m not even depressed!

At least that’s how I thought years ago, when I first tried them.

Odd that your concern is for something (hallucinogens breaking out of the lab and onto the streets) that you acknowledge already happened (“they’re pretty much available everywhere”). How is that an argument against researching therapeutic potential? Your comparison to methamphetamine falls flat, meth is legal and regulated (desoxyn), and we give it to children. Our finest scientific methods continue to show that psychedelics are safer, have fewer side-effects, and have better long-term results than just about any prescribed medication. The problem isn’t with plant medicines that fostered the evolution of human consciousness, the problem is with the puritanical brainwashing that suppressed them in the first place and continues to taint our collective unconscious.