This interesting article recently appeared in JAMA Psychiatry. It concerns the difference that use of newer high-potency marijuana can make, in terms of associated mental health and addiction problems in adolescence (and beyond). A controversial topic, granted. But with a recent influx of new research, one that seems to be yielding its secrets to science.

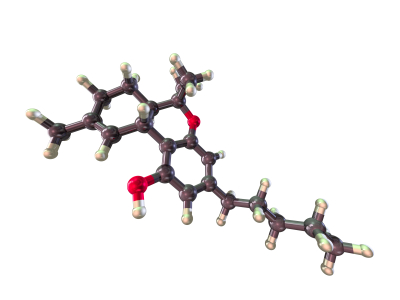

The study was done in the UK, and involved more than a thousand participants who reported cannabis use in the preceding year. The experiences of those who used the high-potency stuff (THC content above 10%), were compared with those of users who stayed with lower potency varieties.

The research team found that using the more potent forms substantially increased the risk for cannabis use disorders (CUDs in the US), as well as anxiety disorders. When used frequently, higher THC pot also appeared to significantly increase risk of psychotic symptoms, tobacco dependence, and other illicit drug use.

Here’s a bit of good news: It did not elevate the user’s risk for depression or alcoholism, in comparison with lower THC marijuana.

The conclusion, in their own words: “Limiting the availability of high-potency cannabis may be associated with a reduction in the number of individuals who develop cannabis use disorders, the prevention of cannabis use from escalating to a regular behavior, and a reduction in the risk of mental health disorders.”

I doubt most people in the addictions field will be surprised. We’ve all wondered about the impact of vaping, solids and oils on the prevalence of SUDs. Selfishly, perhaps, because many will no doubt be involved in the cleanup. But the fact remains that it’s plain frustrating to see new problems allowed to flower before the old ones are even close to over.

As the researchers put it: “Policy liberalization has been accompanied by proliferation of high-potency cannabis in legal markets, and THC concentrations have increased in markets where cannabis remains illegal.” Translation: Doesn’t much matter whether your state has actually legalized cannabis – the pot will get a lot stronger regardless.

THC’s effects are dose-dependent, so frequency as well as potency is often a key factor in the emergence of mental health and/or addiction problems. In my experience the typical person in outpatient treatment uses more than once a week, and often daily. Their drug use is likely to be in combination with other substances as well. And they’re attracted to stronger varieties – from ordinary weed to “skunk” etc., and on to “wax”, “shatter” and other solids.

Researchers where cannabis is fully legal have noted a measurable increase the number of adult daily smokers — the prime candidates for treatment. But the popularity of vaping among youth seems to have carried liquid cannabis into that dimension as well.

As usual, many questions remain unanswered. Since the high potency stuff appears to worsen rather than relieve anxiety, why do so many folks swear by it as a treatment for PTSD? Is the cannabis actually doing something else entirely, such as relieving withdrawal symptoms from cannabis?

That’s what happens with alcohol and opioid disorders. The patient winds up self-medicating drug withdrawal, believing it’s the solution when in fact it’s become the problem.