How to Identify and Treat Patients With Substance Use Disorders

A recent feature in Medscape confirms it: Our physicians frequently run into problems when it comes to identifying and treating patients with substance use disorders.

Who’d have guessed? Okay, we all would. Partly because there are so many doctors who complain about it.

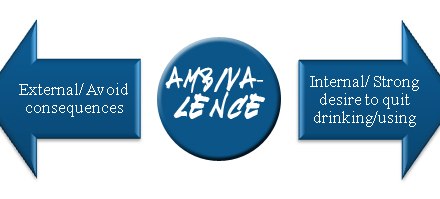

“Look, when I first started practicing,” said one family practitioner, “I tried doing what they told us to do in training. I brought up evidence of an alcohol problem with the patient and politely inquired if perhaps he thought he might be drinking a little too much. And you know what? The patient got mad and stormed out of the office. I never saw him again. And I’m afraid that was also the last time I tried that approach.”

So what does he do nowadays? “Avoid the subject, mostly, Unless the patient brings it up first.”

I guess that’s one strategy — pretend it doesn’t exist. Another, from a physician at a busy clinic: “As far as I’m concerned, there’s simply no time to delve into a subject like that in the space of what amounts to an 11 minute office visit. It’s not fair to me or to the patient to try. So unless drinking is the main issue behind the patient’s complaint, it’s easier just to let it go. Maybe have some brochures in the waiting area. How to get help, that kind of thing.”

This one came from a specialist: “I see lots of older patients so yeah, plenty have problems with alcohol. But no, as a rule I let it slide. Unless there’s a prior history of problems in the chart. Then I’ll follow up. I might advise the patient to stay away from alcohol for a while.”

Advice that I suspect is simply ignored.

I’ve also heard complaints about alcohol and drug problems being outside the physician’s expertise. “I’m not a psychiatrist. I’ll refer a patient to a good psychiatrist if they ask for it. Otherwise it’s not my responsibility.”

If such reluctance is common, then I suppose it’s easy to explain why so many cases have to reach the point where the ER or a hospital admission is involved. And of course, many people with alcohol problems simply avoid seeing the doctor altogether, if they can.

How prevalent are SUD’s, both drug and alcohol, in medical practice? Studies have suggested up to 40%, depending on the population.

“You have to understand,” an office nurse once told me. “Primary care is not set up to deal with these people.” I do understand. Frankly, it’s amazing that as many SUD patients are referred for treatment as there are, given the obstacles involved.

Think about how primary care operates. In the waiting room, the patient may be asked to fill out a form about health history, current complaints, etc. If you do have a question, you can approach the desk and ask for guidance. When finally ushered into the inner sanctum, a nurse will take your vital signs and collect more info. When at last the doc arrives, you’re into the intensive phase of the visit. A few minutes to check your medication, ask some more questions about your health, then you hop up on the exam table for a quick going-over. Maybe there’s an order to be written, a prescription to be adjusted. Before you know it, the visit’s over. Don’t forget to stop at the desk on your way out.

I get that it would take a special kind of practitioner to overcome these natural barriers to get at an SUD that may lie underneath. Even when he or she strongly suspects there is one.

I fear we may never have enough of those special practitioners to go around.