From the New York Times:

This City’s Overdose Deaths Have Plunged. Can Others Learn From It?

I happened to attend college near Dayton, Ohio, and even in the late ’60s there were real concerns about heroin use in the city. At the time, rumor linked the drugs to smugglers using the military planes that arrived at a nearby Air Force base. Supposedly the drugs were concealed in body bags. I have no idea if that turned out to be true. But everyone agreed that whatever the source, heroin was far too readily available.

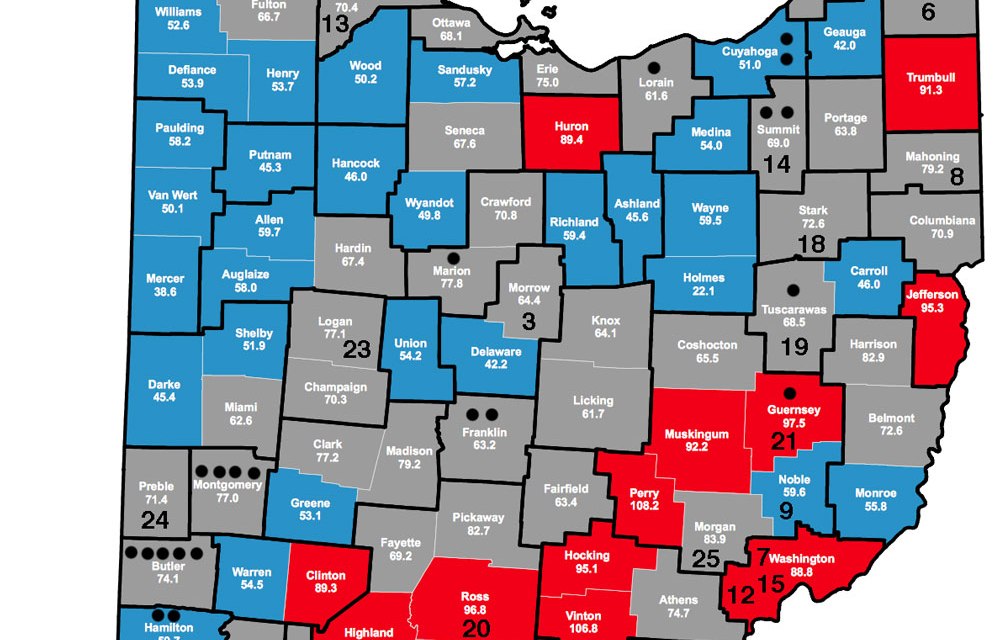

So it’s not a big surprise to me that fifty years later, Dayton is still among the hardest hit cities in one of the hardest hit states. Yet the number of fatalities sank to half the previous year’s total.

What changed? Several things.

One was a decrease in availability of carfentanil, the horrifically potent synthetic that had somehow found its way into the street drug supply. As usual, no one knows precisely where the drug had come from, or where it went. But the impact on OD rates was real: even a little of the stuff, used as an adulterant, can be enough to kill. Health authorities remain vigilant in case it makes a reappearance, perhaps added to a different class of drugs, such as coke or meth.

There’s broad consensus on the importance of the other big change: Expansion of Medicaid. Suddenly, people in the city had access to a host of services that were previously unavailable. New providers moved into town. Treatment became more accessible, to a far broader and more diverse segment of the populace.

Ohio’s Republican governor had to go against the wishes of many in his own party in order to accomplish this. Here’s hoping the families of Ohio are suitably grateful.

In an epidemic the size of this one, with 50,000-plus deaths annually, it isn’t smart to let political orthodoxy interfere with practical healthcare. You either make necessary compromises or suffer the consequences. Or more likely, force your citizens and their families to suffer them.

Don’t worry, there’ll still be plenty of time to argue ideology later on. But when people are falling over dead in the streets– well, that has to come first.

Why are you showing 2013 data? What to compare to? I will no longer trust politicians to analyze data.