By hardcore, I’m referring to a patient who presents with an established history of multiple unsuccessful treatment episodes. It’s a term borrowed from the literature on drunk driving. In that it’s often used to describe offenders who accumulate multiple DWI arrests in a relatively brief span.

What the two have in common: Each accounts for a disproportionate share of the damage done to others.

If you’ve been in the treatment field for any length of time, you’ve surely run into examples of the chronic relapser. “Ralph is like flu season,” a nurse told me about a recent admission. “He comes around a couple times a year. If you work here, you’ll run into him.”

I’ve long been fascinated by this phenomenon. Possibly that’s because I began my career in hospital-based treatment. Residential rehabs are also a popular landing spot.

I was a guest speaker at one such facility and at the conclusion of my talk, an older man in the front row asked a question. “What advice would you give to somebody who’s been in rehab 32 times?” Everyone in the room laughed except me – they knew he was talking about himself. I did my best but I think he pitied me. I just didn’t ‘get it’. He was hopeless.

He wasn’t really hopeless, of course. But he was convinced he was.

Hardcore relapsers are a diverse group but there are common features. Among them:

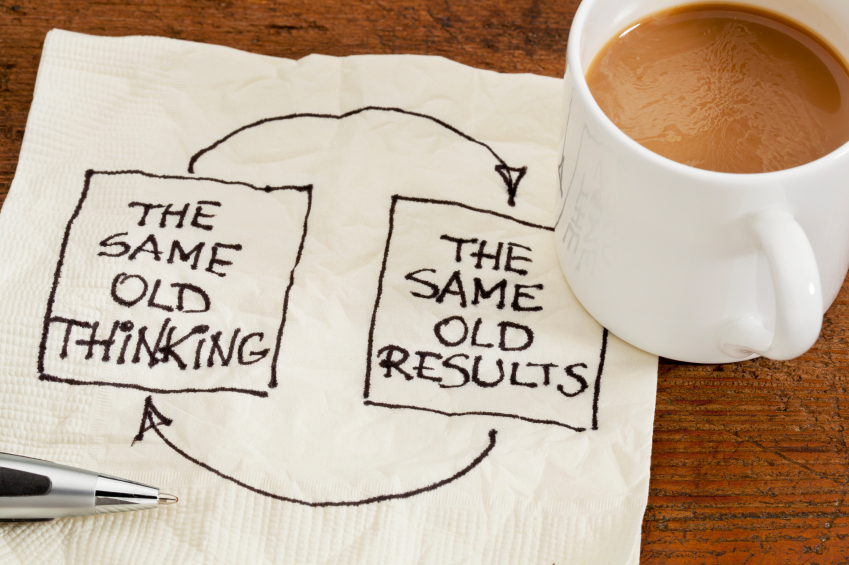

- A tendency to repeat the errors that they have made before, without recognizing it.

- A deep-seated lack of faith in their own ability to change (understandable).

- Often, some secondary benefit to their relapses. It may take some searching to identify it, but it’s probably there.

Family and clinicians may operate in the belief that a fresh start is what’s needed. But for certain patients, a fresh start is just a chance to make the same mistakes all over again. That’s what we need to prevent.

Here’s an example. Justin is a retired college professor with serious cardiac disease (three open heart surgeries in the past) and multiple prior treatments for alcoholism. His pattern has been to do well post-discharge for three to six months, then, for no apparent reason, go on a binge that lands him in the hospital again. With his history, that usually meant ICU. The family was worried and so was the RN case manager at his insurance company – those hospital bills mount up. The figure I heard quoted was over a million dollars.

Everybody wanted this to stop. Including Justin. Or so he claimed.

To make a long story short, turned out that the solution was fairly simple, and emerged about halfway through his stay, through a conversation that another patient then reported to their shared counselor. Justin wasn’t really interspersing long periods of abstinence with binges. He began drinking again soon after discharge. He had been remarkably successful at hiding that fact – didn’t hurt that he lived alone – but it was only a matter of time before he lost control and went on yet another bender.

“It’s like somebody who pretends they’re not stealing when they’re really just not getting caught stealing,” said his eldest son in dismay. Good analogy. The result may look the same, for a while. But it isn’t.

Over the years I’ve heard many reasons given for secret drinking or other drug use. A couple examples:

“I never stopped craving it. I’d be okay for few days but then I’d be wanting it again. I figured other people wouldn’t understand. I needed to cheat. And you have to admit, I got away with it. For a while.”

“A drinker since I was fourteen, I was supposed to stop now? Because I had a few problems? Give me a break. I went along to get along. But I always knew I would drink again someday. And if that was the case, why wait? I knew I could lick it if I kept trying.”

It’s an illustration of what I’ve heard called the war within, an ongoing conflict between the drinker and the drug, one that has yet to be decided.

In that respect, I suppose the rest of us – family, physicians, counselors, judges – are really bit players.