Pseudoscience is usually defined as an approach or method that appears to be based in science, and is presented as such, but in reality doesn’t meet the standards for legitimate scientific findings.

It’s sometimes difficult to distinguish, because after all it’s designed to look and feel like the real thing. In other cases the difference is just painfully obvious.

What makes science? The scientific method. That involves observation, hypothesis, experiment, analysis of results, and replication — followed by peer evaluation using an established hierarchy of evidence. It’s a complex process, one that to a degree is self-correcting, and there’s always room for debate. Advocates of pseudoscience take advantage to promote their questionable practices.

Most of us have some degree of trust in Science. When done correctly, scientific investigation yields findings that are measurable, factual, and largely objective. But our native trust means that simply by wrapping themselves in the trappings of science, some very questionable theories can be made to seem authoritative. An example: creationism or ‘intelligent design’, which isn’t really science at all, but is often portrayed as if it were. Or the theories of Freud, heralded as a ‘scientific’ explanation of behavior that never actually qualified as such. Recognizing this doesn’t cancel out their important role in our cultural heritage. It does mean we shouldn’t pretend they’re based in science.

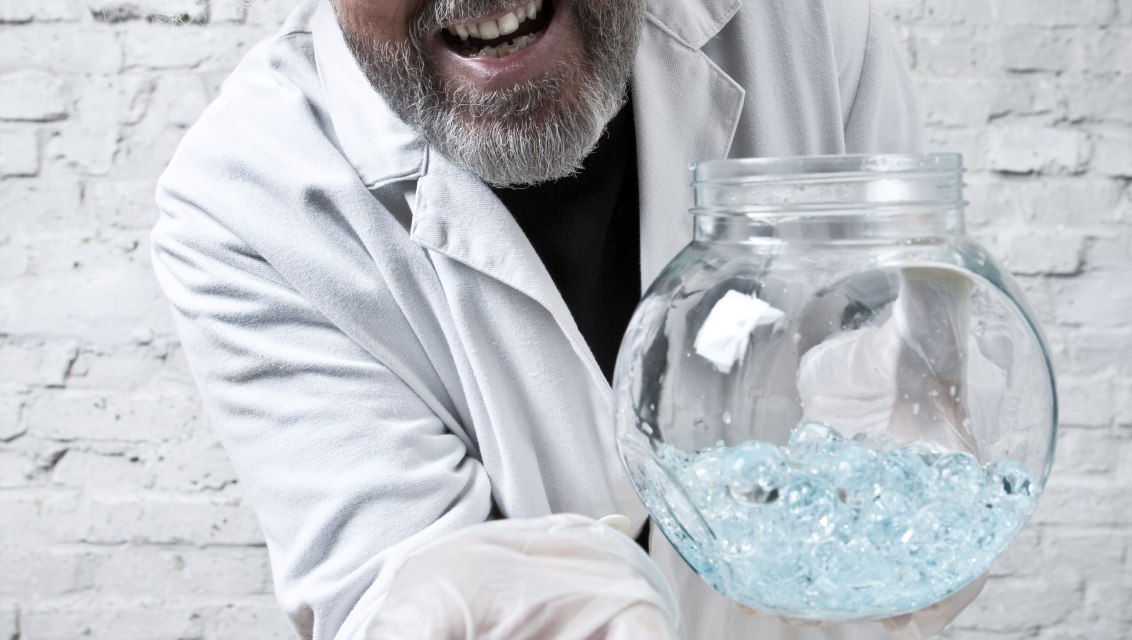

Addiction has always attracted its share of loony theories, simply because of the absence of a cure. Seems like every theory has its devotees and heartfelt testimonials. To a passionate believer in pseudoscience, this is like waving a red flag in front of a bull. They’re already convinced of the universal superiority of their favored approach. It takes very little to set them howling “I have it! Over here! Look at me!” And invariably, some people fall for it.

Often this is nothing more than a harmless waste of time and money on something we should have seen wouldn’t work in the first place. In other cases, it leads genuinely sick people down a garden path.

For instance, there’s a new field of study called epigenetics, defined as the study of heritable changes in gene activity which are not caused by actual changes in the DNA sequence — a way for certain factors in the environment to affect heredity. It’s already been co-opted by pseudoscientists to ‘justify’ an assortment of nonsense notions. One of those is that by changing one’s thinking patterns to align more correctly with ‘quantum’ energy patterns (don’t ask me to explain that), we can prevent or even cure cancers. Or our addictions, which seem minor by comparison.

These explanations are presented in the language of science, in order to gain additional authority with the public, but quickly crumble under scientific investigation. That’s pseudoscience.

That’s what we in the treatment field have to watch out for. The treatment population is jam-packed with vulnerable people and families desperately looking for magic solutions to a genuinely challenging problem like recovery. They don’t always listen to us– after all, we don’t have any magic– but it’s still our responsibility to try.

Another link on differentiation:

http://www.quackwatch.com/01QuackeryRelatedTopics/pseudo.html

It’s not always easy, but here are a couple sites that do a pretty good job of it, staffed mostly by medical professionals… you can use their search box to find things.

http://www.sciencebasedmedicine.org/

http://www.quackwatch.com/

Do you have any advice on how folks may identify pseudoscience?