I came across an odd quote in an article on patients with illnesses that mean they will have to be maintained on opioids indefinitely. No surprise there; I’ve met a few myself. But the article quotes an eminent pain specialist, who said:

“If you’re on opioid medication for a long period of time, you become dependent…When a need becomes a want, that is really an example of when someone can become addicted. When you want it and you can’t live without it, can’t survive without it, it interrupts your day to day life, that’s addiction.”

First off, withdrawal symptoms can appear after only a few weeks of use. They worsen over time. More importantly, addiction isn’t the result of abuse. Addiction drives abuse. The symptoms the physician describes aren’t the beginning of addiction, they’re a later stage.

We’ve all heard that nobody sets out to become addicted. It happens beneath our awareness. People “wake up” to the reality of addiction– perhaps because bad things start to happen.

Addiction’s a brain disorder. It’s this same addicted brain that the specialist says will help the user differentiate between needing and wanting a drug. In reality, it will feel as if you want it because you need it. And there’s no objective measure that allows us to say with certainty when you crossed a line into a mysterious land called ‘addiction’.

That’s what made the notion of pain as a ‘fifth vital sign’ a practical impossibility. A doctor can measure your BP, pulse, temp and respirations. For pain, the most he can do is ask the patient how he feels. Or use that smiley face thingy. It’s almost entirely subjective.

A physician has no reliable way to predict that a given patient will have problems with the opioids she prescribes. Unless the patient has a history of substance problems, of course, and decides to bring it to the doctor’s attention during that 10-15 minute office visit.

Besides, what warning would a physician provide? “Look here, Percy, if you start to feel addiction coming on, schedule an appointment, will you? Could be important.”

I guess the idea is that up to that point, the patient was fine.

Lots of people sitting in recovery programs will tell you that they weren’t warned about the risk of addiction to prescription meds. They trusted the person prescribing them. “I was already forging Vicodin scripts before it occurred to me I was addicted,” said one. “I just felt like I needed more.”

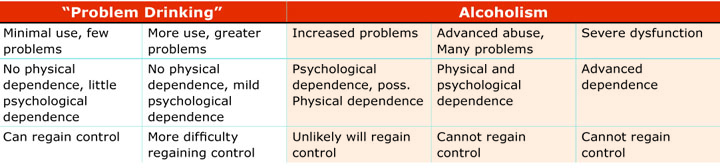

The flaw in this very late-stage view of addiction– which was also a huge problem when it came to getting doctors to recognize alcoholism in their patients — is the suggestion that somehow, addiction is the patient’s fault. Avoidable if the patient simply followed directions.

Physician: “Evelyn, be careful that your life isn’t completely disrupted by these drugs I’m about to give you.” No, that doesn’t sound right either.

Maybe it’s this essential misperception that explains how we in the US came to consume 80% of the world’s prescription opioids. We understand the benefits. We underestimate the risk.