Eminent neurosurgeon and 2016 GOP Presidential candidate Ben Carson recently spoke out on the subject of addiction, here.

Some of the quotes gave me a weird sense of being back in the 80’s during the era of “Just Say No”.

But was I surprised to hear such opinions voiced by a respected physician? Not at all. I’ve heard far worse. And I’ve long wondered about the origins of unscientific views held by otherwise competent doctors.

A couple possible contributing factors:

- We have a tendency to think of physicians as men and women of science, but that isn’t strictly true. Over the years, I’ve come to view clinical docs as healthcare practitioners with specific medical training– not the same thing at all. At least half of modern medical practice is not evidence based, let alone grounded in good science. That helped me understand why so many outlandish remedies have been advocated by qualified medical people. My conclusion: Some clinicians are real scientists. Many are not.

- Physician training hasn’t focused much on addiction. You may have heard Dr. Pursch’s admonition that in 4 years of schooling, students spent 2 hours on addiction– the number 1 problem they’d face. Medical school curricula have improved in that respect. Still, many current practitioners completed their training well before it did.

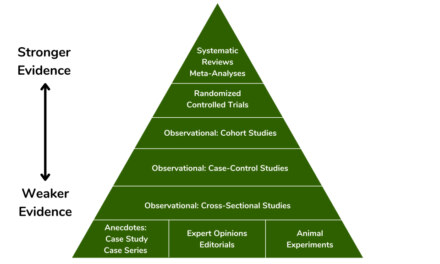

- Research can be misleading. Physicians are flooded with research, some of questionable value. A recent article on nutrition science looked at a study that involved only 55 subjects, followed for only 2 weeks, yet its ‘conclusions’ drew extensive media coverage.

- Doctors have always struggled to understand and treat addiction. For centuries, physicians viewed alcohol and drug addiction as a ‘self-inflicted’ disorder rooted in weak will and a lack of moral values (in that sense, Carson’s views aren’t new). Of course, if addicts really were weak-willed, it would be a heck of a lot easier to convince them to get treatment. Hospital care focused on short-term detox with an emphasis on returning the patient to the street as quickly as possible. If by chance the patient didn’t fit the physician’s preconception of an addict– he or she was a respected member of the community, for example– then the doctor often fell into the enabler role.

You’ve no doubt encountered horror stories of physicians involved in celeb deaths, like Elvis and Michael Jackson. As one doc explained to me, he knew he was feeding an addict’s habit, but figured if he didn’t provide the drugs, the addict would just find them on the street, in more dangerous circumstances. It’s a convenient rationalization that ignores the reality that the doc isn’t actually ‘giving’ the drugs away, he’s selling them, using the insurance company as payer.

I don’t have any straightforward proposal for remedying this, other than to acknowledge that many competent physicians are perhaps the worst people we can go to for advice about our own situation or that of a family member. So when someone asks me for guidance, I take care to point them to a physician or practitioner who genuinely knows something about the subject.