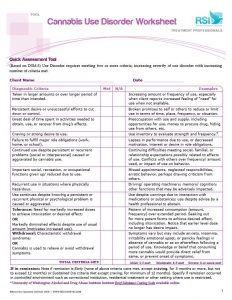

Cannabis Use Disorder, the DSM5 option for treatment of persons addicted to marijuana, may present some unique challenges to those seeking to diagnose it. On the surface, things don’t sound that difficult– you need only two criteria over a 12 month period to qualify, with the presence of additional criteria meriting a ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’ description.

But the criteria can be confusing. They’re subjective enough to make it easy to for anybody who doesn’t particularly want to be diagnosed to avoid it. Let’s take a look:

Cannabis often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than intended. The user is asked to determine whether s/he planned to smoke that much pot. “I guess so,” I can imagine someone saying. “I did it, didn’t I?” But at some point, a user might look back and think about the other plans foregone and activities uncompleted.

Persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control cannabis use. Same problem as above– did the user genuinely want to cut down, or just thought maybe s/he should?

A great deal of time spent in activities necessary to obtain cannabis, use cannabis, or recover from its effects. Pot isn’t like crack or heroin– you don’t need to go broke or devote your life to its pursuit. It’s like cigarettes. Something most users do frequently. Finding the kind you like. The stuff with just the right THC content and the perfect “high.” Finding places to smoke, people to smoke with…

Craving. We have some pretty good instruments for measuring craving, (try the University of Washington Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute (ADAI) Brief Substance Craving Scale), but beyond that we run into the classic problem of differentiating between ‘drug hunger’ and using something because you really, really like the way it makes you feel– which is technically quite normal.

Recurrent use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. People do miss work or school– too “relaxed” to care, too stoned to attend. A user trying to be responsible might take themselves off the list to drive or operate machinery. If you worked at some company that required a security clearance and flunked the drug test– that will qualify.

Cannabis use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by cannabis. It certainly makes sense that if you suffer from a major mental illness, you should stay away from pot. Unless of course it’s been prescribed by your physician as an aid to dealing with your emotional discomfort.

I hesitate to bring up the whole medical marijuana mess, except to share a recent story from a friend who suffers on and off from anxiety and disrupted sleep. “Are you on medical mj?” inquired his physician during a recent visit. My friend admitted he wasn’t. “Well, I’ll write you a prescription anyway,” the doc said, shrugging. “You might want to try it.”

Update:

On November 8th, 2016, the states of California, Massachusetts, Maine, and Nevada passed referenda to legalize the sale of cannabis for recreational use. Those states, plus an additional twenty-four (including New York, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Florida) and the District of Columbia, already permitted the prescription and dispensing of cannabis for various medical uses– and the criteria and ease of obtaining such prescriptions virtually assured any adult willing to pay a “marijuana doc” can get legal access to the drug.

It doesn’t take a psychic with a crystal ball to predict that, given current trends in cannabis consumption, an upsurge in problem use will be rolling into the addiction treatment business soon.

The attached tool is based on the DSM5 criteria, it includes examples and a checklist for assessment. Although intended for clinicians’ use, it can also be self-administered by anyone worried about whether their cannabis use is entering ‘problem territory’:

Scott: I think you underestimate the addictive power of cannabis. It is possible to binge on it and to become obsessed with it to the exclusion of all other activities or interests. It has a withdrawal syndrome that can be very debilitating. It is worse for young teenagers who should be studying and playing sports rather than walking around stoned all the time. Going to school stoned interferes with daily activities. Playing sports stoned is not fair to your team. Driving while stoned and thinking it is not impairing is another common behavior, which can lead to accidents. Going to work stoned is not fair to the employer. One can get to the point of not caring at all about other activities and dropping out of sports, not going to class or doing homework. One can avoid working because one doesn’t want to be tested. Why should an otherwise healthy teenager use “medical marijuana” instead of learning to cope? Marijuana interferes with REM sleep so even if one can sleep, it disrupts the natural cycle. Using it several times a day can ultimately lead to psychotic symptoms. Marijuana is not like cigarettes at all in the above respects. I say this from witnessing this behavior and much more. I’ve heard from those who failed in college classes because they were constantly stoned and couldn’t learn but only realized this after quitting. Cigarettes are not healthy but they don’t interfere with motivation, concentration, or performance.