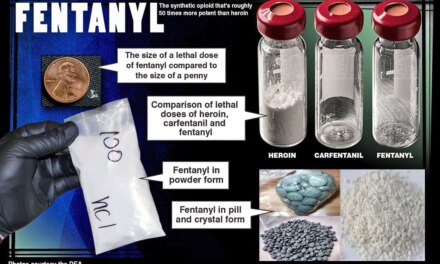

I’m sure it won’t surprise anyone at this late date to learn that fentanyl, the powerful synthetic opioid once used primarily to treat cancer pain, has now become the driving force in an opioid epidemic that simply refuses to go away.

I recall one prediction from a commentator that drug cartels, being essentially business enterprises like any other, would surely take steps to avoid killing off too many of their own customers. Apparently, he was wrong.

Instead, they seem to have increased the presence of fentanyl in the supply, dramatically escalating the risk of death from overdose. The DEA now claims that some 40% of tested samples contain enough fentanyl to prove fatal to a user.

This surge in fentanyl represents a ‘third wave’ of the opioid epidemic. The first wave involved prescription painkillers (we’re litigating that one now). But while steps were being taken to curb prescription abuse, many of those users, now thoroughly dependent, were already moving on to street drugs like heroin. And just as that trend began to slow, here came fentanyl – far and away the deadliest we’ve encountered. So far, at least.

Does this sound familiar? An echo of a different pandemic, featuring a certain new variety of coronavirus?

It’s this that makes predicting the future so challenging. Just as a new COVID variant seems to spring up right when we’re gaining ground on its predecessors, something similar occurs with drug epidemics. There are literally thousands of possible synthetics that could be game-changers in terms of the opioid wars. We know they’re out there. We don’t know which ones, if any, will emerge from the crowd. Or when, or exactly where. Still, as the street people say: if it can be done, it will be done. Only a matter of time. Our task is to be as ready as we possibly can.

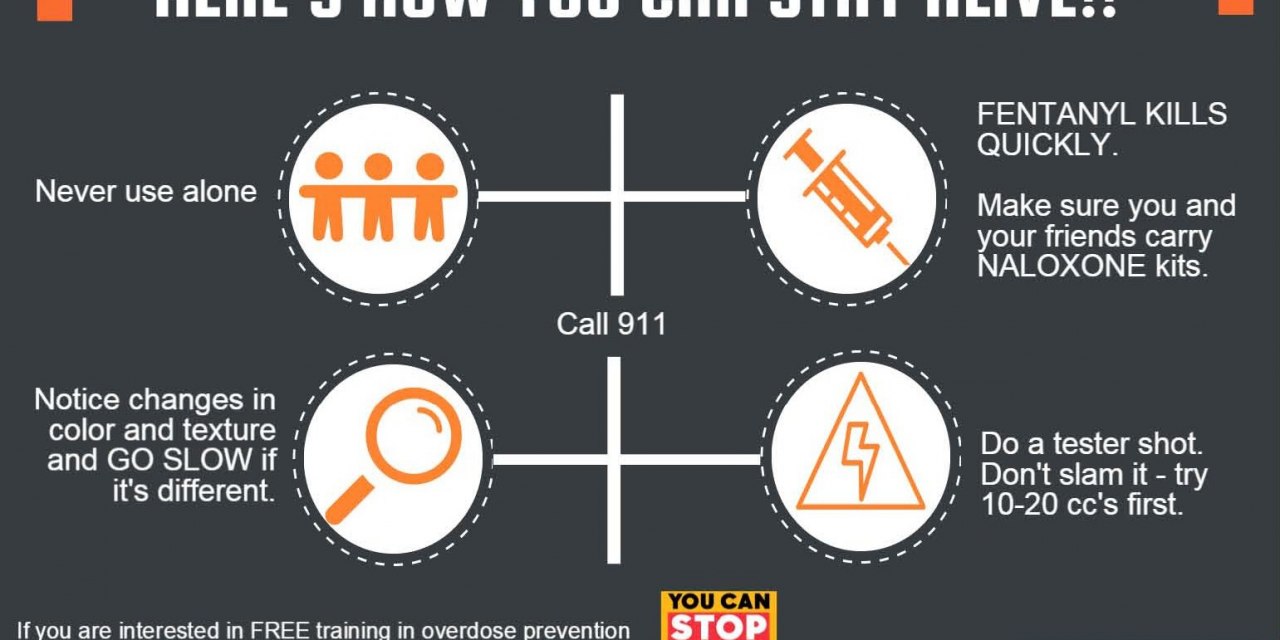

To protect as many lives as possible, health authorities have shifted focus to harm reduction. For instance, needle exchange programs were used to reduce transmission of other diseases via the practice of sharing dirty needles. Now we have supervised injection sites, intended to prevent fatal overdoses among chronic users. Both have been shown to be effective in their limited roles. Still, every time one is proposed, there are plenty of objections.

The two most common:

Aren’t these programs just going to encourage our youth to experiment with drugs? According to research, that doesn’t happen. Besides, I’m not sure kids in the modern era require all that much encouragement to try drugs, beyond what’s already available.

Won’t it attract undesirables to our neighborhood? Frankly, if your local Health Department is recommending such a program in your areas, it’s likely to mean the vicinity is already experiencing drug problems.

For instance, take this fairly innocuous proposal now before our State Legislature.

Bill could clear way for legal use of fentanyl test strips

The idea isn’t new or particularly difficult to grasp. Apparently, many of the people who used (and perhaps died from) fentanyl didn’t realize they were using it. They thought they were using something else — heroin or cocaine, for instance. So why not provide them with a tool to identify the presence of fentanyl in the pill or powder they’re planning to ingest?

Makes sense to me. “Users can employ the strips at home,” the article explains, “by dissolving a small amount of a pill or another substance they wish to test in water, then soaking the strip in the solution. Much like a pregnancy test, a line appears on the test to indicate the presence of fentanyl or one of its many variations.”

Surprisingly, test strips were excluded from the original drug control legislation, on the unlikely grounds that they were actually ‘drug paraphernalia’. Don’t ask me to explain that. But now, with the advent of fentanyl and the resulting cascade of fatalities, we need more and better ways for users to protect themselves from the unintended overdose.

“But that won’t solve the drug problem,” opponents protest. Of course not, but it will save lives. “Not everybody will take the time to test their drugs before they use them,” according to the opposition. No, but enough users will to make a difference in the death totals.

It’s harm reduction, not harm elimination.

And saving lives should be enough justification.