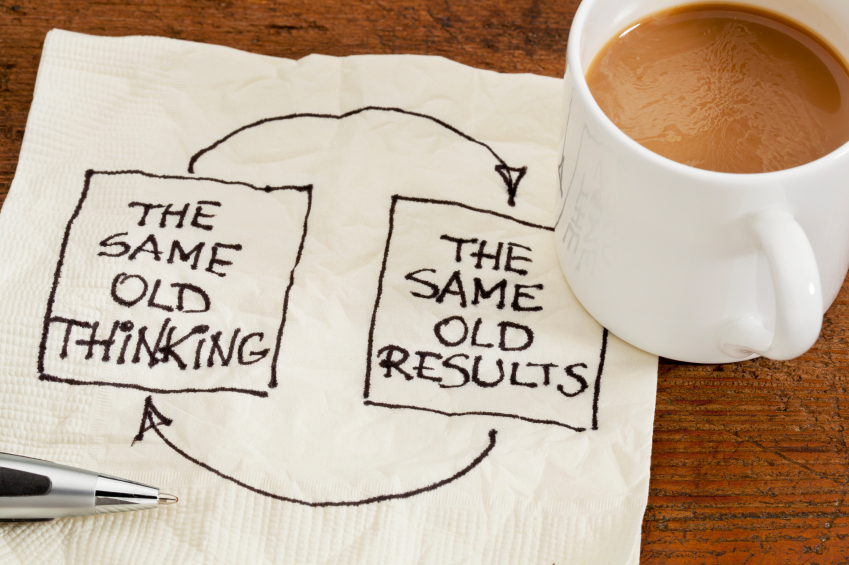

I found this fascinating — an opinion piece from a recovering person, about a debate that’s been going on for as long as I’ve been in the field.

It’s over the definition of ‘sobriety’ – and what qualifies someone for the term.

I’m Regular Sober — Here’s How I Feel About Demi Lovato Being ‘California Sober’

There’s no paywall, so I encourage you to give it a look.

Where I’m coming from — my first years in the field were spent in the detox/rehab unit of a psychiatric hospital. Every patient who didn’t arrive with an attending physician (the majority) had to be assigned one at admission. In practice, that meant one of six or seven practitioners. All the docs at the time had been trained in psychodynamic therapy, the dominant model in psychiatric institutions at the time. Nursing and technician staff were there to provide patient supervision and support. ‘Counselors’, as we know it today, didn’t yet exist in that setting. It was doctor-driven.

Most of the physicians were open about their belief that addictions were rooted in personality problems that began in childhood – something important that had (or had not) occurred during key developmental stages. If the substance of choice was alcohol, that usually resulted in a treatment plan leading to weekly individual talk therapy sessions. If the drug was heroin (probably 20-30% of our census), it was taken as a matter of faith that the patient suffered from a serious character disorder that wasn’t amenable to psychotherapy and instead required long-term care in a therapeutic community (rarely acceptable to the patient), or methadone maintenance, which was considered an innovative approach at the time.

It may not surprise anyone to learn that neither was all that successful. Our alcohol patients tended to drop out of therapy without paying their bills. The methadone clients of the time, those who didn’t drop out, often showed up a few months later, in need of detox for a serious alcohol problem.

One important point: both approaches, drug-free and opioid maintenance, held out the possibility of a return to ‘social’ drinking.

That was all about the psychiatrists’ faith in the power of dealing with the supposed root cause(s) of someone’s substance problems. According to theory, once the patient gained sufficient insight, the drive to abuse drugs or alcohol would recede and eventually disappear.

Because you would once again be ‘normal’, see?

That was a heck of a carrot to hold out to an addicted patient. They jumped at it. For most, it didn’t end well, “I had high hopes for her,” one psychiatrist confessed. “I’m sure she could have made it. She seemed to have gained so much insight.”

Anyway, it was a big step forward when the program beefed up its schedule of recovery meetings and began to strongly recommend abstinence. People still struggled, but it was clear that those who followed that prescription did better than the ones who didn’t.

Much has changed over the years. Cognitive behavioral therapies do work better than psychoanalytic approaches, which isn’t saying all that much. We’ve learned a lot about grief and trauma, and the medications we use appear to have improved. But the rules still haven’t changed signficantly. The path from addiction still involves abstinence and hard work in a recovery lifestyle.

Or as the late Sandy B. put it during one memorable talk: “I’ve been sober for fifteen years now, and I owe it all to — not drinking.”