I’m sure you’re aware that the COVID pandemic, despite our advances in vaccination and treatment, continues to produce new variants that show up unexpectedly to threaten the health and safety of people all over the world. In past epidemics, these variants have proved to be less dangerous than the originals, leading to an overall decline in severity of the illness that follows. Unfortunately, COVID 19 seems to have successfully bucked that trend — yielding new forms of the virus that are every bit as infectious and damaging as their predecessors. Or more so.

I’m wondering if you’ve noticed the similarities between that and our current drug epidemics. We’re dealing with the variant phenomenon there, too.

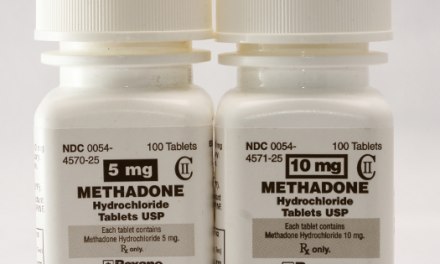

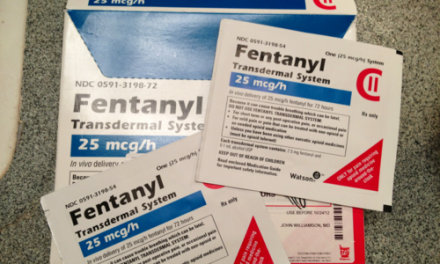

Prescription painkillers may have helped start the opioid epidemic in the US, and street heroin kept it going, but both seem to have given way to the most dangerous opioid yet: fentanyl. Cheaper to make, easier to mix in with other substances, it’s taken opioid abuse to a whole new level.

Something similar has been happening with another ‘old favorite’ — methamphetamine. The variants may represent a new way to make meth, or a new source for key ingredients. As with opioids, the results seem to arrive in waves. As one wave recedes, another makes its appearance. The cycle begins all over again.

The first to draw attention is P2P. In a subsequent post, we’ll look at a second shift in the meth market, born of the discovery of a new plant-based source for ephedrine, the key element in meth-making. That shift could guarantee a near-unlimited supply of the drug in the future.

About P2P – first, a link to an excellent piece by Sam Quinones, author of Dreamland, that appeared in The Atlantic near the end of 2021. I recommend you read it:

‘I Don’t Know That I Would Even Call It Meth Anymore’

In 2006, US pharmacies were directed to remove the popular decongestant Sudafed from open shelves, storing it instead behind the pharmacy counter. so customers would be forced to ask for it. That was because ‘outlaw’ chemists were using the ephedrine inside Sudafed capsules to make meth for sale on the street.

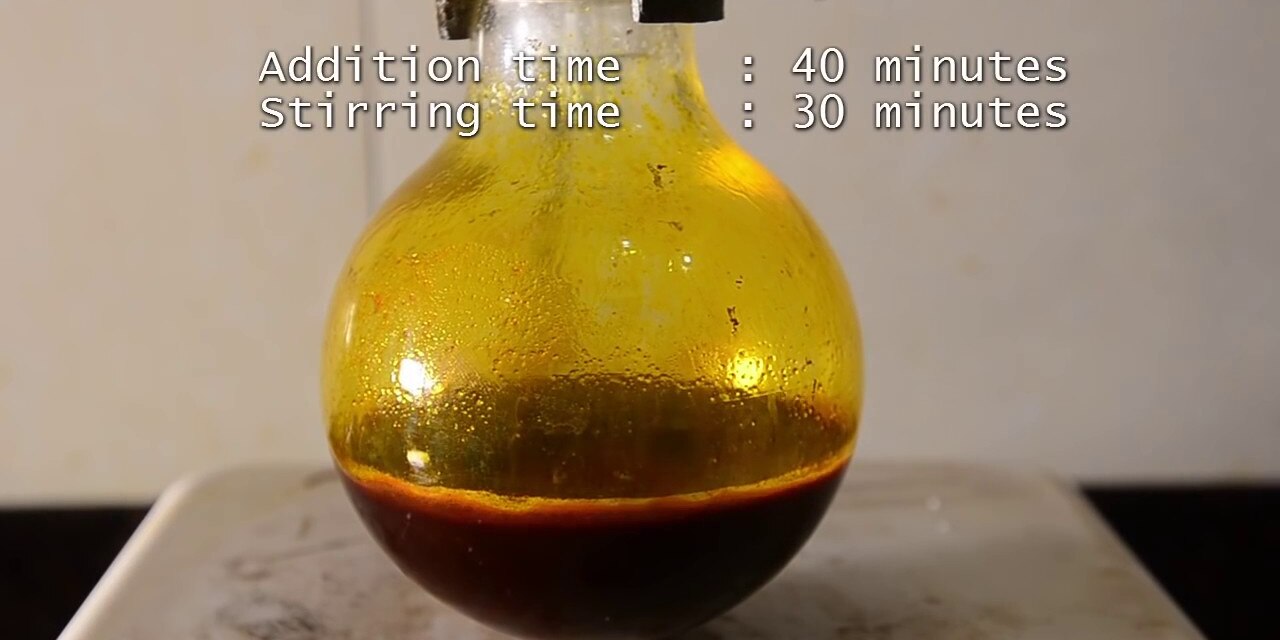

It worked better than anticipated. Frustrated by the sudden lack of access to ephedrine, drug traffickers were elated to discover an alternative method for making meth, one long in use by outlaw biker gangs, who supported themselves with drug sales. The alternative was based on phenyl-2-propanone — abbreviated P2P. But the bikers’ methods of manufacture were both time-consuming and, often, dangerous. Further breakthroughs were required, to vastly improve the process.

Eventually, a ‘new meth’ emerged, in the form of a true synthetic made inexpensively in labs, in quantities barely imaginable twenty years earlier. Most of the new meth would be produced in Mexico, often in commercial labs, then shipped north to the US via the same ports and points of entry used for smuggling marijuana and cocaine. From the trafficking standpoint, it was nearly perfect.

There was one problem, however. It took a while to surface, but there appeared to be a serious downside to the P2P-based meth. For one thing, it seemed to accelerate the curve of addiction, meaning users lost control and deteriorated far more quickly than with ‘old style’ meth. And they suffered more, as well — including a kind of mental ‘toxicity’, in the form of a brain syndrome that featured confusion, hallucinations, paranoid delusions, and episodes of violence.

It was the need to minimize these consequences that motivated users to try speedballing, Meth was combined an opioid, traditionally heroin, but now often something cheaper, like fentanyl. The risk of overdose, including the fatal type, rocketed upwards.

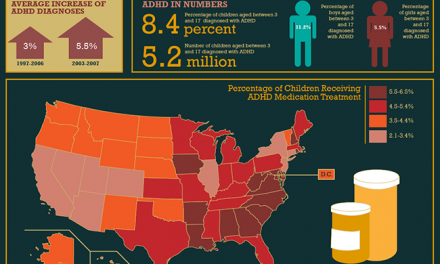

Experts have begun to worry that the popularity of New Meth, given its effects on the brain, will contributed to the dramatic increase in rates of mental and emotional illness that we face now.

That’s the first of the bad news. Soon we’ll follow up with a look at what’s coming out of Afghanistan.