Everyone I know in the addictions field acknowledges the difficulty involved in helping someone into recovery from long-term dependence on opioid medications.

For one thing, ‘long-term’ may in practice mean many years or even decades of regular maintenance on opioids. A behavior pattern so deeply ingrained can be extremely resistant to change. In fact, many patients will have attempted to get off opioids before, on their own or under medical supervision, only to fail miserably. And repeatedly.

So why try again? Often, it’s only because of some outside threat to the supply. Perhaps the physician who has been the source of the medication is retiring, and the replacement doc is unwilling to continue. It happens.

This situation becomes the immediate source of the patient’s motivation for change. But unless it is eventually replaced by internal incentives, relapse remains a strong possibility. And that kind of internal strength can be difficult to find.

Given these barriers, we recognize that no intervention is ever likely to approach a 100% success rate. Even in the very best of circumstances – and those are seldom available — real challenges remain.

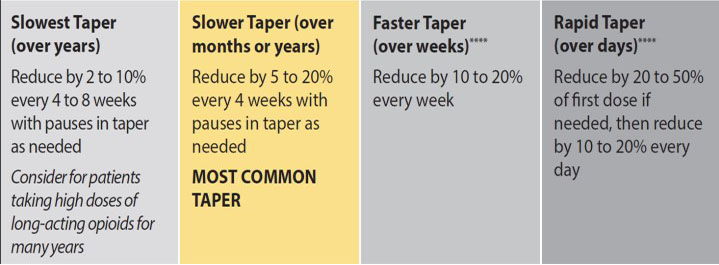

Now for some better news: the evidence suggests an extended taper off opioids can hold up better than a more rapid approach. Instead of simple cessation of use, the opioid is deliberately reduced on a preset schedule. The goals being to:

- Minimize the severity of withdrawal symptoms that may follow, and the stress that accompanies them, while

- Giving the patient more time to adjust to a new kind of life.

The desired outcome can be abstinence from opioids, or continuing maintenance using an opioid substitute, such as buprenorphine or methadone.

That’s something best determined via cooperative decision-making involving both patient and practitioner. A certified addictionologist is often best prepared to supervise the tapering itself, with support from other professionals as needed.

It’s a special kind of intervention that benefits from special expertise and experience.

I came across one research project from the UK that looked at the relative success of this sort of individualized approach. The mean age of the study population was 61 years; 60% were female. In addition to the medically supervised taper, participants received group therapy, mindfulness training, and other supports.

The process was a simple one: a 10% reduction in the patient’s baseline opioid dose every week, until the patient reached 30% of the original dose. After that, a further 10% reduction of that dose, on a weekly basis. The speed could of course could be adjusted if withdrawal symptoms proved troublesome — the point being to achieve the goal of stable recovery, rather than to stick to a specific timetable.

Of those who remained in the program — and there were inevitably dropouts — 30% remained abstinent at one year. That may not sound like much, but it’s several times the rate of the control group.

No, it’s a long way from perfection. But a step in the right direction.