Here’s something new on a proposed Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) protocol for methamphetamine users. Until now, there hasn’t been one. That’s something of a handicap given that:

- Meth disorders have a reputation for being notoriously difficult to treat, in terms of the usual recovery goals;

- Though meth can be ingested orally or smoked, a significant percentage of users will inject the drug intravenously. That leaves them at elevated risk for STDs and HIV, adding another level of urgency to intervention and treatment.

- Worse still, meth use appears to be on the upswing, more so in some parts of the country than others. Per the 2020 National Survey, some 2.6 million Americans (age 12 and up) reported using meth in the previous 12 months. That’s a significant number.

All this explains the interest in new treatments. An example, from an article in The New England Journal of Medicine:

Bupropion and Naltrexone in Methamphetamine Use Disorder

I’ll highlight a few key points.

- First, the study was a two-stage trial involving adult users with moderate or severe Methamphetamine Use Disorder (MUD) – 400+ of them in Stage I, 225 in Stage II. They were drug tested frequently over a period of 12 weeks to measure their response to the regimen, versus placebo.

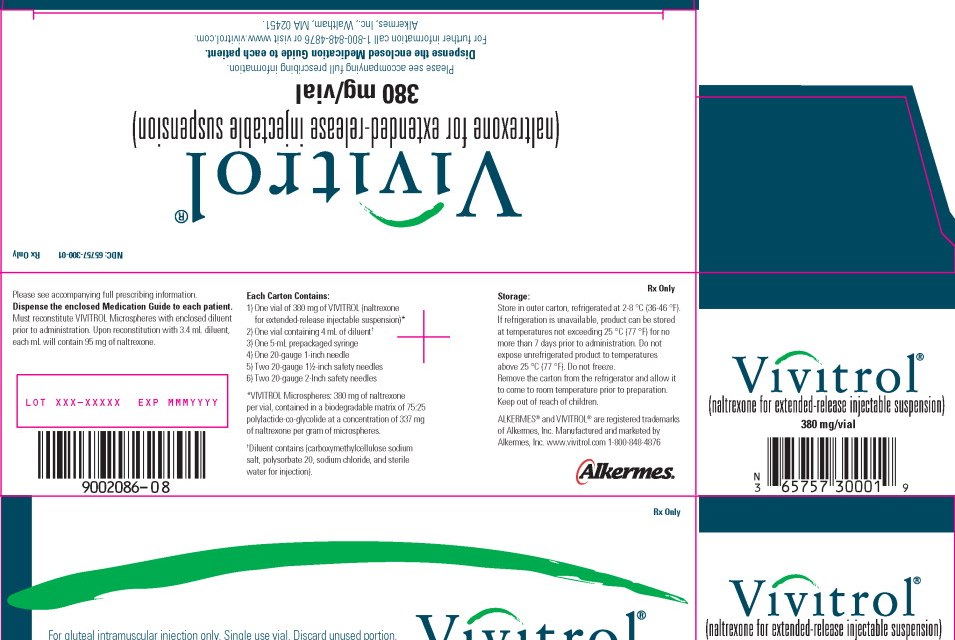

- The medications: “extended-release injectable naltrexone (380 mg every 3 weeks) plus oral extended-release bupropion (450 mg per day).”

- You may be more familiar with them under their commercial names: Vivitrol (naltrexone) and Wellbutrin (bupropion). Naltrexone is an antagonist used for both alcohol and opioid disorders; bupropion is an atypical antidepressant. Neither had previously been used specifically for methamphetamine patients.

- By the way, the naltrexone is administered via gluteal injection every 3 weeks. It isn’t self-administered; a professional is required.

Now for the response:

- “The weighted average response across the two stages was 13.6% with naltrexone–bupropion and 2.5% with placebo, for an overall treatment effect of 11.1 percentage points”. That’s certainly a statistically significant difference in favor of the medication.

- The overall rate of response, however, would still be considered low. Definitely better than nothing. Still, I suspect most clinicians were hoping for something more widely effective.

One obstacle to adoption of the new regimen would be expense. A quick glance at current costs puts injectable naltrexone at $1775 per injection, for a total cost of $14-15K annually. Unless the expense was covered by insurance or private funds, that could be a deal-breaker, no question.

In my experience, methamphetamine users often arrive in treatment already having exhausted their own resources. If Medicaid, for instance, expanded approval of naltrexone injections to include methamphetamine, that would make the combination more useful to addiction treatment. Until that happens, however, price is actually the bigger barrier to use than the combination’s relatively low rate of effectiveness.

I mean, how do you justify prescribing something that costs a lot and isn’t all that likely to work?

Of course, if the price of naltrexone were somehow lowered, that would change the equation substantially. Hear that, Big Pharma?

So it’s fair to conclude that this study represents a step forward, but not a terribly big one. More to come, I imagine.