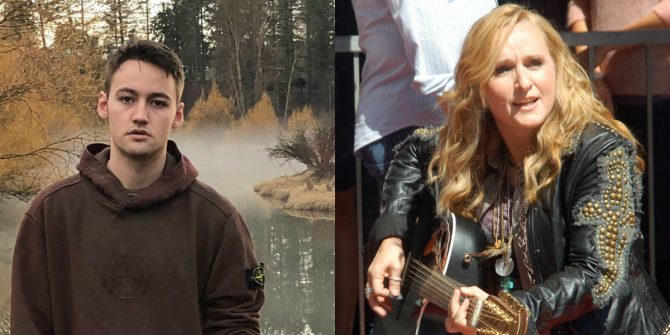

Here’s an interview featuring folk-rock singer Melissa Etheridge as she reflects on the lessons she learned, albeit painfully, from her experience with an addicted son — who died in 2020, at age 21, of an apparent opioid overdose.

Melissa Etheridge says son Beckett’s death ‘taught me that I cannot save anyone else’

It’s a familiar story: a talented young athlete introduced to painkillers in the aftermath of a serious injury, finally succumbing to addiction after four years of struggle. As expected, his family did everything they could to stop the slide — including multiple attempts at intervention, rehab, and support. All were, in the final analysis, to prove unsuccessful. The end came with the overdose. It may not have been his first, either.

This outcome is a more immediate risk for drug users than in the past, due to the omnipresence of fentanyl, carfentanil, and other synthetics. The risks themselves, however, aren’t new. They’re the same ones families of addicts have faced for many generations now. The drugs, they may change. The dilemma of addiction? It stays the same.

I don’t know how many times I’ve met with a family in panic, convinced that if they don’t do something, anything, right now, it’ll be too late. That anxiety often results in an impulsive decision leading to another failed attempt at intervention. In hindsight, they wonder if they moved too quickly.

But at the moment, it felt as if they had no choice.

In my experience, such situations are challenging but far from hopeless. A little additional time spent planning and preparing often makes all the difference. That of course means exercising patience, and patience is never easy for a family in crisis.

It helps to remember that the experience of addiction may have already damaged the lines of communication and trust within a family, making change that much more difficult. A few of the early traps that families fall into:

- Attempts to control the user with threats or manipulation – these usually fail, and when they do, contribute to an adversarial atmosphere of blame and resentment.

- Sending mixed messages — families often seek advice from multiple sources, some well-meaning but misguided, some just plain wrong. The result is more confusion and self-doubt.

- A credibility gap can emerge, between what the family says they will do or want, and their own past behavior. Promises not kept, threats not carried out, agreements abandoned too quickly – that suggests that any future moves will be viewed skeptically by the substance user, and probably tested as well. “Yeah, that’s what they say, but do they mean it? Because they didn’t the last time.”

Hint: Simply insisting that ‘you’re not bluffing this time’ isn’t enough to convince someone of your determination. They may insist on being shown how much you mean it.

In an atmosphere that’s already been ‘spoiled’ by prior negative experiences, it’s essential that a family’s actions going forward be well thought-out and carefully planned. Rushing around from crisis to crisis will only create still more barriers to overcome. And undermine our own best efforts.

First step: Slow down. Take a few steps back. Make sure that you’re getting the best available advice (hint; it’s out there, it’s really about finding it) and once you do, try following it. That alone doesn’t ‘fix’ addiction. But it does make it possible for all the other steps you’re about to take to have the desired effect on the user.

As for the experience of addiction, and of families forced to deal with it, I might recommend two companion books: Beautiful Boy by David Sheff, and Tweak, by his son Nic. Essentially the same story, told from two very different viewpoints within one family. It makes it easier to see how communications can go awry.

Worth your time and attention.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks