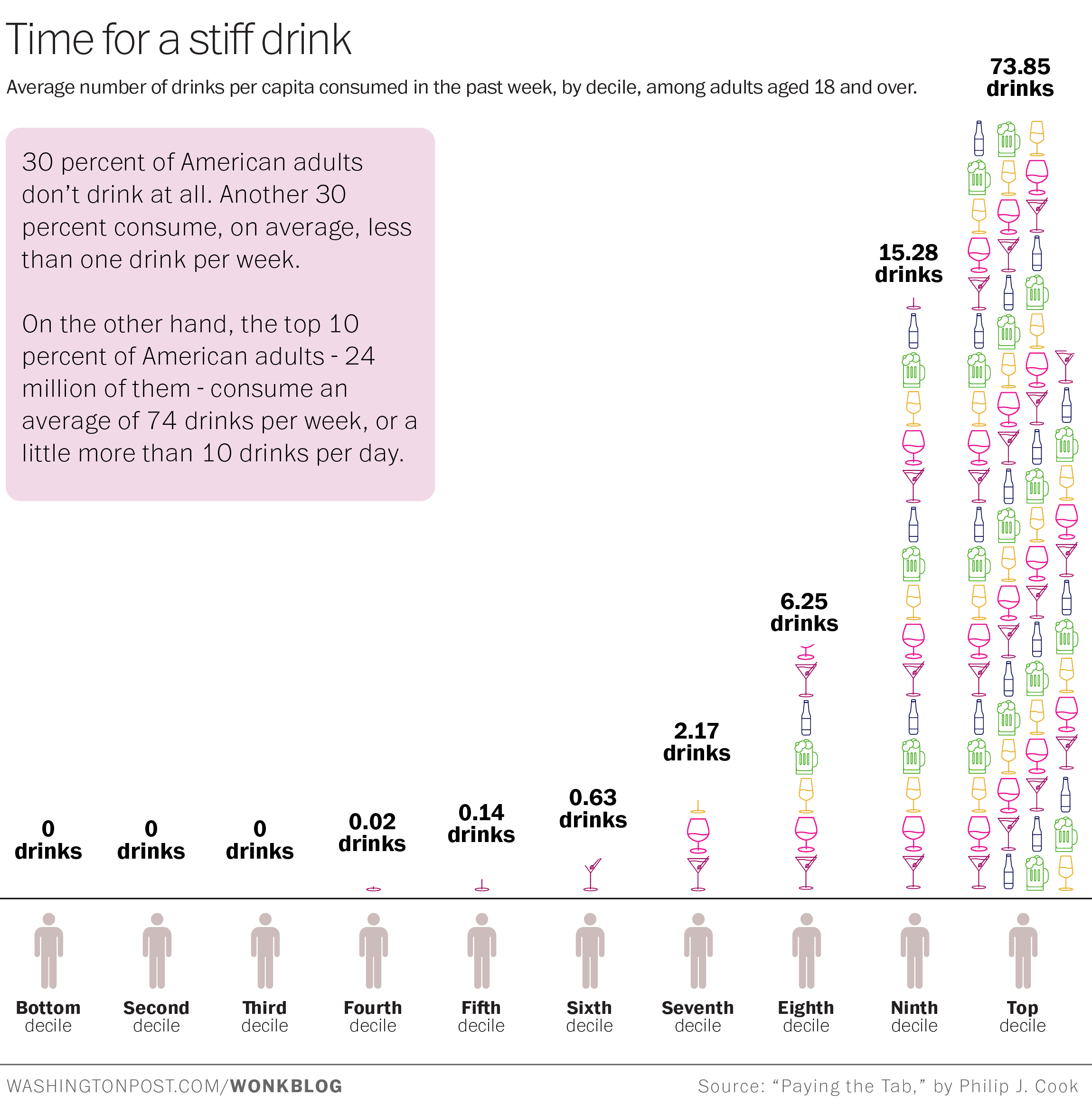

Here’s an interesting blog from the Washington Post on how American adults drink. It’s based on a 2007 book. Check out the chart:

There’s something at least mildly unexpected at both ends of the continuum. First, that 30% of Americans don’t drink at all. And another 30% average considerably less than a drink per week. In practice, that translates to many weeks that pass with no alcohol consumption at all. We might refer to that group as ‘virtual nondrinkers’.

The other surprise: apparently, 10% of American adults– around 24 million– average more than 10 drinks a day. Remember, that’s an average– there may well be days on which they consume much greater amounts.

Simply counting daily drinks, long a favorite of some researchers, isn’t the best way to measure what we call ‘alcoholism’. There are plenty of alcoholics who drink infrequently but go on extended binges when they do. And there’s evidence that some drinkers consume less than average and nevertheless suffer significant consequences. Vaillant noted that a more reliable indicator is the presence of problems in several areas of life, related to drinking. Work and marriage, for instance, or school and psychological health.

Still, most patients who enter therapy for addictions probably come from that 10% on the far right of the scale. There’s been some criticism of the field for focusing too much on the severe cases, but that’s predominantly who shows up in treatment (they have the motivation). Doesn’t make a lot of sense to design your clinic to serve people who aren’t asking you for help.

We may see a similar pattern of use of marijuana in the event of true legalization — meaning availability at levels with some restrictions, comparable to alcohol and cigarettes today. A significant percent of the population would abstain entirely or use very infrequently. Another group, far smaller but still significant, would qualify as heavy users. Even now, with restrictions in place, we’ve heard estimates of 6 million Americans who use pot every day. Logically, that number would increase.

I imagine many in that group will qualify for a DSM substance use disorder diagnosis. They’ll be experiencing disruptions in work and school and home and health comparable to the current crop of alcoholics.