E.M. Jellinek’s book The Disease Concept of Alcoholism appeared in 1960. Jellinek reviewed a broad spectrum of available knowledge from the perspective of a social scientist rather than a physician or psychologist. He advanced the idea that so-called alcohol abusers could actually be divided into five broad categories:

The Alpha was psychologically but not physically dependent on alcohol. Alphas might show signs of loss of control on some occasions but at other times were able to control drinking.

Betas were not dependent, but showed signs of alcohol-related medical problems such as liver disease.

The Gamma drinker was the type normally associated with alcoholism — someone who was both physically dependent on the drug, and also experiencing loss of control.

The Delta was physically dependent, but lacked obvious signs of loss of control.

The Epsilon drinker’s problems were intermittent in nature, mostly in the form of binges in response to situational stress.

Jellinek’s formulation attracted interest because of three advantages over others of the time.

- It represented the first real typology of alcohol abusers

- It suggested that the vast population of ‘alcohol abusers’ was actually heterogeneous, with considerable variation in behavior and experience

- Jellinek managed to include drinkers whose abuse was periodic. They had often been excluded from discussion.

Jellinek believed that Gamma and Delta alcoholism represented a disease process, while Alpha, Beta, and Epsilon patterns did not. In his typology, most AA members of the time were Gammas forced into sobriety by escalating loss of control. Where Gamma and Delta drinkers would eventually need to give up alcohol entirely, the other three types could (in some cases at least) conceivably return to ‘normal’ drinking.

Problems with Jellinek’s typology quickly emerged. In reality, alcoholic drinking patterns often changed dramatically over the course of a lifetime. An Alpha might develop symptoms of withdrawal. A Delta would eventually lose control. So-called Betas often turned out to be drinkers who underreported their consumption and the problems it caused. As a result of such issues, Jellinek’s categories faded from common use.

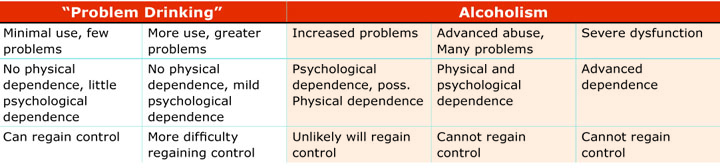

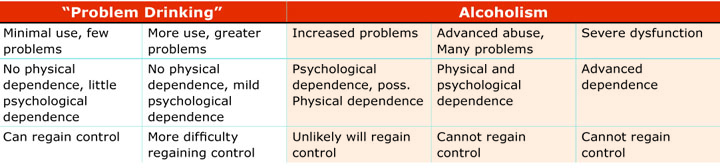

Psychiatrist George Vaillant used the results of a landmark study to modify the disease concept to suggest that the variety (and persistence) of symptoms was a better diagnostic indicator than the presence of a few specific symptoms. He compared it to another very common disorder, hypertension, and found a number of similarities. His revised continuum, from left to right:

How Models Change

A model generally supersedes other models not because it is perfect in every respect, but because it seems to explain certain aspects better than its predecessors.

For instance, the popular Temperance model of the 19th and early 20th Centuries in America held that alcoholism sprang from sin and temptation and was best treated through ‘pledges’ of piety and church attendance. This was a view that fit easily with the religion of the time but yielded little by way of successful outcomes.

The emerging AA model, on the other hand, attributed alcoholic drinking to allergy and obsession and proposed that recovery could come through its Twelve Step program and the mutual support of other alcoholics. The results of that approach led to renewed hope.

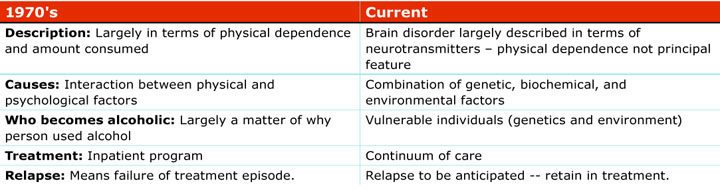

Likewise, a newer Disease model began in the 1960’s to replace older medical approaches to alcoholism. Its characteristics:

But the disease model continued to evolve. A look at yet a newer version:

Summary

Understanding a complex phenomenon is largely a matter of continuing refinement based on new findings and changes in perspective. With alcoholism, this reflects the explosive growth in brain science and genetics. No doubt our understanding will continue to evolve over the coming century.

Nonetheless, it never hurts to remind ourselves that the human brain is the most complex organ we have yet encountered. And however much is learned, a far greater amount is yet to be explored.

Interesting that the table above says the current model says ‘disorder’ which implies something different than disease. Crucial point is current dependence spectrum recognises levels of severity.