Warning: Undefined variable $serie in /home/domains/treatmentandrecoverysystems.com/docs/wp-content/plugins/wp-series-manager/wp-series-manager.php on line 264

When You Love a Shapeshifter, Part 2

The drugs or alcohol have turned someone you love into a monster. How can we turn them back?

Maybe the addict or alcoholic you love has already been through treatment- more than once- and failed to stay clean and sober. If you’ve seen this, it can be easy to lose faith in the possibility of recovery. But do not give up hope: Addictive disease can be effectively treated at nearly any point in its progression.

The key is believing that addiction is best treated as a disease.

“Well, that’s nothing new,” you’re probably saying right now. “People have been saying that for years.”

True enough. There’s more support now than in the past for regarding alcoholism and drug dependency as a disease process, rather than signs of a moral weakness. And there are many treatment programs and facilities predicated on the view that addiction is a disease.

But there’s a big difference between “knowing” that something is a disease, and actually treating it as one.

For instance,we’ve long recognized the similarities between addiction and diabetes:

- Both are chronic (long lasting)

- Both are progressive (get worse over time if untreated)

- Both are potentially fatal if untreated.

- Both involve a mix of hereditary and experiential vulnerability, exposure to substances, and physiological changes.

- In each case, ignorance of symptoms, and often denial, complicate recognition and diagnosis of the disease.

- In both cases, there is no “cure.”

- Successful treatmend of both involves adherence to a lifelong regimen of treatment, particularly avoidance of certain substances that aggravate the disease (addiction: alcohol or drugs; diabetes: foods high in sugars/simple carbohydrates.)

Given all these similarities, you might expect to see a lot in common in how they are treated. But that’s not yet the case. In many addiction treatment programs, a great deal of effort is spent exploring psychological and interpersonal issues. And while this can be useful (especially in identifying and changing patterns of thinking and acting that will keep the recovering addict vulnerable to relapse,) the emphasis often distracts from a more helpful and important aspect of treatment: The completion of tasks. Task-centered addiction treatment focuses on accomplishing specific objectives in the realm of changing behavior (drinking and drug use.)

Beginning to view the condition of addiction for what it is: a chronic, progressive, primary potentially fatal disease, opens the door to understanding and, through understanding, effective action.

“Chronic” diseases are long-lasting. “Progressive” diseases get worse over time. A “primary” disease is one that doesn’t depend on some other condition for its origin. (For instance, contrary to a popular belief, alcoholism isn’t necessarily a ‘symptom’ of another condition, such as depression.) “Potentially fatal” shouldn’t need much explanation. Addiction kills in many ways, not all of them medical. Most recovering addicts can relate incidents during their active addiction that might easily have been fatal.

There are still plenty of folks who protest that addiction is different from other chronic diseases like diabetes, hypertension, or asthma. “People choose to drink alcohol, or use drugs,” they point out. “Nobody forces them to. Those other diseases are involuntary, there’s no choice involved.”

But billions of people have made the choice to drink alcohol, or smoke marijuana, or use a muscle relaxant or painkiller, with very different results. And we now know much more about how exposure to triggering factors or substances works in other chronic diseases, such as childhood-onset asthma. If you talk to a hypertension patient about their “choices” to eat fatty foods and avoid exercise, you’ll hear the same thing you hear from the alcoholic or drug addict: “If I knew then what I know now, I might have made other choices. But I never thought it would come to this.”

Chronic diseases are a reality, and treating them as a moral failing is not only missing the point, it’s preventing us from addressing the issue (and reducing the costs to individuals, families, and society) by effective treatment.

Common Patterns

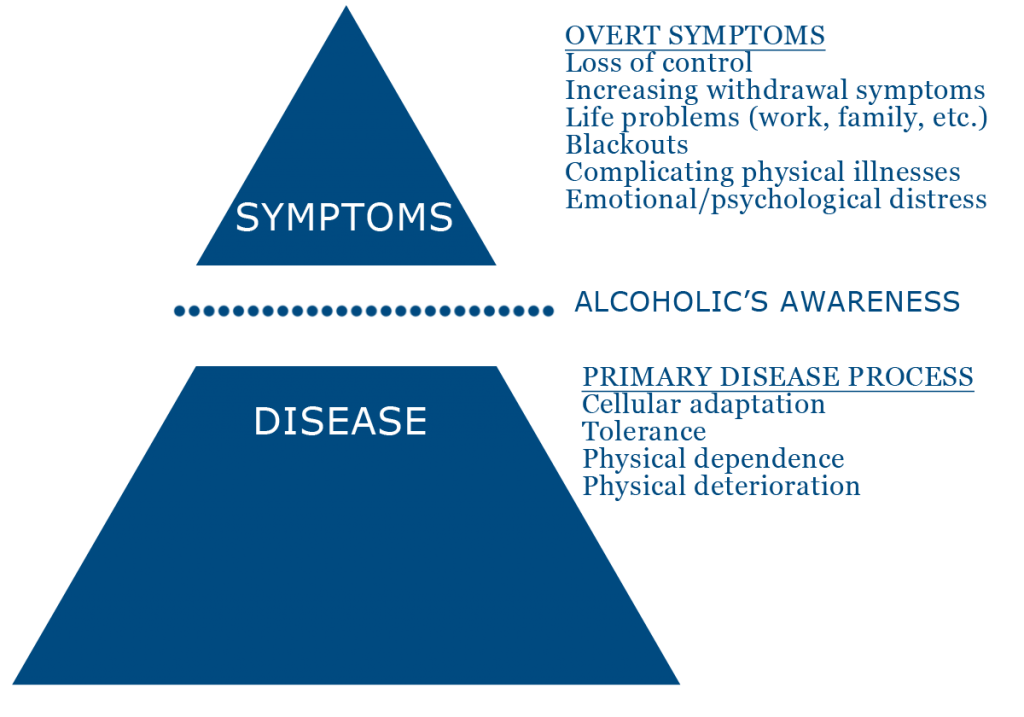

One of the confusing things about “seeing” (and identifying) addiction is the variation in use patterns. Because they differ from person to person, it’s easy to say things like “He goes for days without taking a drink, he can’t be an alcoholic!” or “She was using a lot, but she handled it fine until just recently.” The two most common patterns are:

The maintenance pattern. Here, the drug is used mostly to control withdrawal symptoms. It’s not drinking to “get high,” it’s “using medicine” to function. Maintenance addicts can consume large quantities, and exhibit few signs of obvious intoxication. Their elevated tolerance allows them to appear “normal.”

The other pattern is characterized by loss of control, usually in three key areas: amount consumed, time and place of consumption, and length of the episode of use. It’s easier to spot these addicts, because loss of control usually causes clearly-identifiable problems. But the fact that they “lose” control means that they can also achieve short-lived episodes of control that may be deceptive.

These patterns mingle, and an individual addict can manifest either or both, at various times. If you understand the patterns, and their relationship to the disease, you can also see how it’s influencing the addict’s behavior: The excuses and defense mechanisms they use, the problems that appear in their lives, the responses of family, friends, and colleagues.

The patterns not only serve as clear markers for the disease, they offer a clear prognosis for the future. In spite of widely-varying experience, upbringing, family background, education, character, etcetera, all addicts will have, to a remarkable degree, a similar experience of addiction. Including, tragically, the ultimate endpoint: fatality. Doing nothing can be a death sentence.

We’re not trying to scare you. The fact is, this very predictability also offers hope. It’s our only significant advantage in the battle against addiction: We know what’s going to happen (even if the addict doesn’t.) So we can learn, and we can plan. Whatever our relationship with the addict– as a friend, family, clinician– we can use our knowledge to develop a strategy for intervention, treatment, and supporting recovery.

And recovery, ultimately, can go beyond survival, to hope and growth.

Coming Soon: Your Greatest Fear

[serialposts]

These are posts belonging to the same serie:

Great read! thank you and I hope alot of families get some relief after reading your share. StayBlessed, Jen

“And recovery, ultimately, can go beyond survival, to hope and growth.” …. My (personal) favorite line. Life becomes so, so, so much more than we ever anticipated. All because we were willing to get help and face our self —unaltered.

And I can’t think of a better illustration of that than the many insights you’ve shared in your blog, Lisa. Thanks.