This article first appeared in December of last year:

Carfentanil-Involved Drug Overdoses Soar From 2023 to 2024

Seems that once again, the ‘face’ of the overdose epidemic — that actually began in the 1990’s– could be about to change.

Most experts think of the epidemic in terms of three distinct waves. The first was the result of widespread overprescribing of painkillers, in the mistaken belief that they were safe for long-term pain relief. Next came a surge in heroin use, driven in part by users turning to the street after restrictions were placed on the physician-prescribed opioids they’d come to depend on.

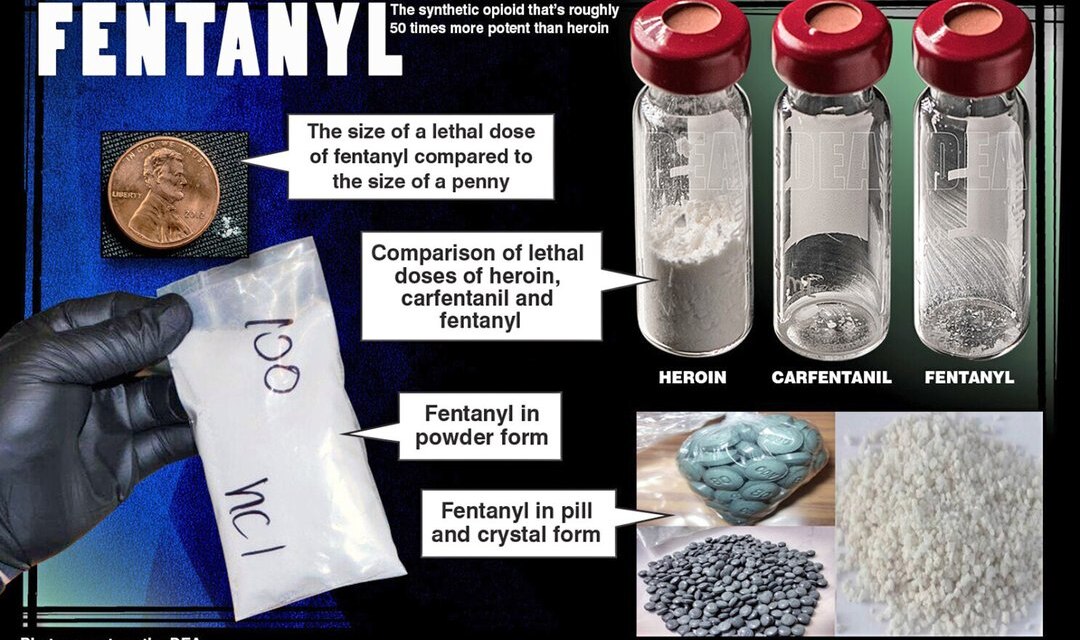

The third wave centered on the introduction of illegally made fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that has dominated our attention ever since.

Will carfentanil become the fourth wave?

This isn’t actually the drug’s first appearance in the US. It showed up in test samples in some areas as far back as 2016-17. That subsided, however, probably due to interruptions in the supply chain.

Now it’s back. “Overdose deaths from carfentanil…[increased] from 29 between January and June 2023 to 238 in that same period in 2024.” That’s a heck of a year-over-year increase, although it still represents only a small percentage of the total fatalities.

Carfentanil is the same super-powerful analog of fentanyl that’s long been used to tranquilize very large animals, such as elephants. Just a tiny amount can prove fatal to a human being. As the article notes, multiple doses of naloxone are routinely needed to reverse its effect — and often, even that won’t be enough.

So far, the government has focused on harm reduction strategies, including distribution of fentanyl test strips and access to drug-checking services.

The latter are common in Europe, not so much in the US. The user (or perhaps the seller) can send a sample to a drug-check firm for analysis. Then at least they’ll know what’s in it.

Perhaps more valuable to society, these same firms often monitor the content of substances currently available for sale and use in the local area.

In research from Europe, it appears that substances the researchers didn’t expect to find were actually more prevalent on the street than the ones they expected.

Translation: increasingly, what the user purchases on the black market is probably not what they believe it to be. There may have been “something extra” added, without their knowledge.

It’s quite possible the seller doesn’t know the exact contents, either.

The opioid users I’ve worked with– mostly chronic, daily users, physically dependent — haven’t paid too much attention to such considerations. They’re too focused on getting something, anything, they can put in their bodies to make them feel ‘normal’ (their term) once again. Meaning temporary relief from the symptoms of withdrawal.

They don’t think much further ahead than that.

It’s the proverbial accident waiting to happen.