Here’s something that went largely unnoticed during the run-up to the vote on the Federal tax cut: a big break for those who make and sell alcoholic beverages.

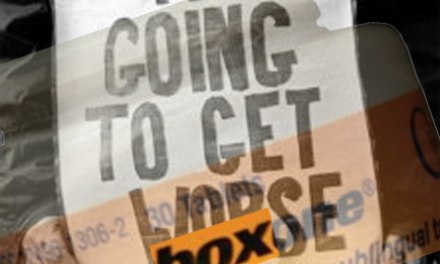

Tax cut on booze triggers fears of more abuse and drunken driving

It’s certainly drawing attention now, from public health types. The liquor industry has long claimed that reduced taxes on their products will not lead to increased consumption. Public health experts, citing research, insist that it will.

Originally, the tax cut for alcohol was advertised as an aid to growth for small craft businesses. But it turns out that the cuts will also apply to the giant industry players. In real dollars, “Big Alcohol” will get by far the largest benefit, simply because they’re so darn big.

It’s the same criticism made of the recent bill as a whole– the greatest benefit will go to those who arguably need it least.

About that research: Scientific literature does seem to provide strong support for the notion that any significant reduction in price will likely lead to a corresponding increase in drinking. I wonder if that means expanded consumption among so-called “edge” groups: Lower income people, or younger drinkers, or seniors and others on a fixed income. People for whom the cost of alcohol is a major limit on consumption.

To allay this concern, the industry says the price of alcohol may not fall much, if at all. In their version, makers and sellers maintain the current price and simply invest the extra money they get in their business, particularly hiring more Americans. I suppose that will happen in some cases, but maybe not for the really large players.

Big Business operates on a different model. As the current CEO of Wells Fargo put it, to CNN: “… our expectation should be that we will continue to increase our dividend and our share buybacks next year and the year after that and the year after that.”

Sounds like more money for shareholders and salary and bonuses for execs. Can’t blame them, can we? These folks work for their investors. But it’s not a way to create new jobs in the good old US of A.

Something to consider: Average consumption is skewed towards either end of a continuum.

The 10% of Americans who qualify as heaviest drinkers consume an estimated 74 drinks a week, or 10-11 per day. On average. No doubt some weeks they consume less, and other weeks a whole lot more. The next 10% average 15 drinks a week, a big drop, but still an important segment to anyone who is marketing alcohol.

At the opposite end, however, are the 30% of Americans who don’t drink. Their motives include religious and cultural beliefs, medical problems, psychological issues, and of course, recovery from addiction. To a marketing exec at a big distiller, these folks are like people who pay off their credit cards every month– “deadbeats”, because they produce no revenue for the alcoholic beverage industry.

This brings me back to those “edge” consumers, less affluent and younger customers. Increasing their consumption is one way for the industry to expand its customer base. Of course, those users have fewer resources to pay for healthcare and legal problems that often result from more drinking. So who picks up the tab? The taxpayers, say the experts.

Think back to the appearance of crack in the mid-80’s. Its low price helped attract a whole new demographic to cocaine use.

Well, the bill’s already passed, so in that sense it’s too late. Still, some experts urge states to take their own steps to offset problems before they materialize. Raise the State tax, for example, or restrict sales to fewer locations. I imagine any such moves would bring quick negative response from the alcohol industry.

As far as they’re concerned, that’s their money now.