You may have heard or read about scandals involving recovery homes, which over the past decade have become a fixture in many cities and communities. Some are extremely well-run, a real asset to folks new to recovery. Others are, well… not.

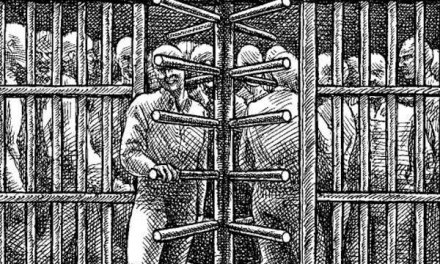

‘Pimping out’ drug addicts for cash

By the way, the problem isn’t exclusive to addictions– mental health has its issues as well.

If you work in treatment, this won’t come as a complete surprise. In many states, recovery homes have not been subject to that much oversight. Where regulations did exist, they often went unenforced due to staff cutbacks at agencies that would ordinarily monitor them.

My first exposure to the recovery home movement came through generally positive contacts with the Oxford Houses. If you’re not familiar with them you can check them out here.

I thought the Oxford model worked pretty well. To begin with, it was nonprofit, and the homes themselves were self-governing and affordable, with flexible stays and clear boundaries around further substance use. But as demand for homes increased, more entrepreneurial ventures popped up. Some of those failed to live up to expectations– either because they didn’t understand how a home should be run, or because they didn’t care. Meaning they were in it for the cash.

From the late 1970’s on, inpatient stays were in steady decline. That was the influence of managed care. The emphasis shifted to a quick transition from residential to outpatient. Ironically, at the same time, the patient population was also in transition, from primary alcohol users (mostly middle-class and employable), to street drug users, including crack and polydrug clients. Many were from low-income backgrounds and brought with them multiple social and economic problems that defied short-term solutions. Since inpatient treatment was no longer an option, something else would have to fill the gap.

One option was a recovery home. The intent was to provide a safe, supportive environment where people could get and hold jobs and participate in outpatient care.

The reality is that for someone who lives on the streets or in a homeless shelter, it’s going to be a real challenge to stick to a treatment regimen. It’s just not a lifestyle that promotes sobriety and stability.

Then the 21st Century came. With an opioid epidemic in progress and a resulting explosion in overdose rates, it became even more essential to get users into a controlled environment for an extended stay. Thus the proliferation of recovery homes. Once again, this could work well, but was clearly vulnerable to abuse.

That abuse usually came in one of three forms:

First, kickbacks. A home would seek or receive payment for referrals, perhaps from a treatment provider or a medical clinic or a drug testing lab.

Second, a home would be lax when it came to substance use by residents, which led to some predictably tragic incidents.

Third, fraudulent billing practices to take advantage of third party funds– a problem for healthcare in general.

That’s why monitoring and enforcement are essential. We still need recovery homes, perhaps more than ever, in spite of the problems some experience. We need to ensure the safety and security of those who reside there. It’s not the sort of business that naturally self-regulates. That’s what government is for.

Granted, it’s a big task, but I don’t see any shortcuts.

Enjoyed this truthful piece on recovery homes. I’m in the Southern Cal area and things are getting shaken up here with all three of these abuse tactics. It reminds me of the true freedom I possess—today—because I am authentic and “practicing the principles” in ALL my affairs.

The road less traveled might not be as glamorous, but it sure is peaceful and constant. Living in fear of getting caught for unethical practices is a fear I never want to have.

You often touch on a topic that is current for me. Thank you for your never ending devotion to this blog.

Lisa

You’re most welcome, Lisa! We are always glad to hear from you. We’ve had to be a bit more careful about monitoring comments, so we hope you and others will stick with us until the trolls tire.