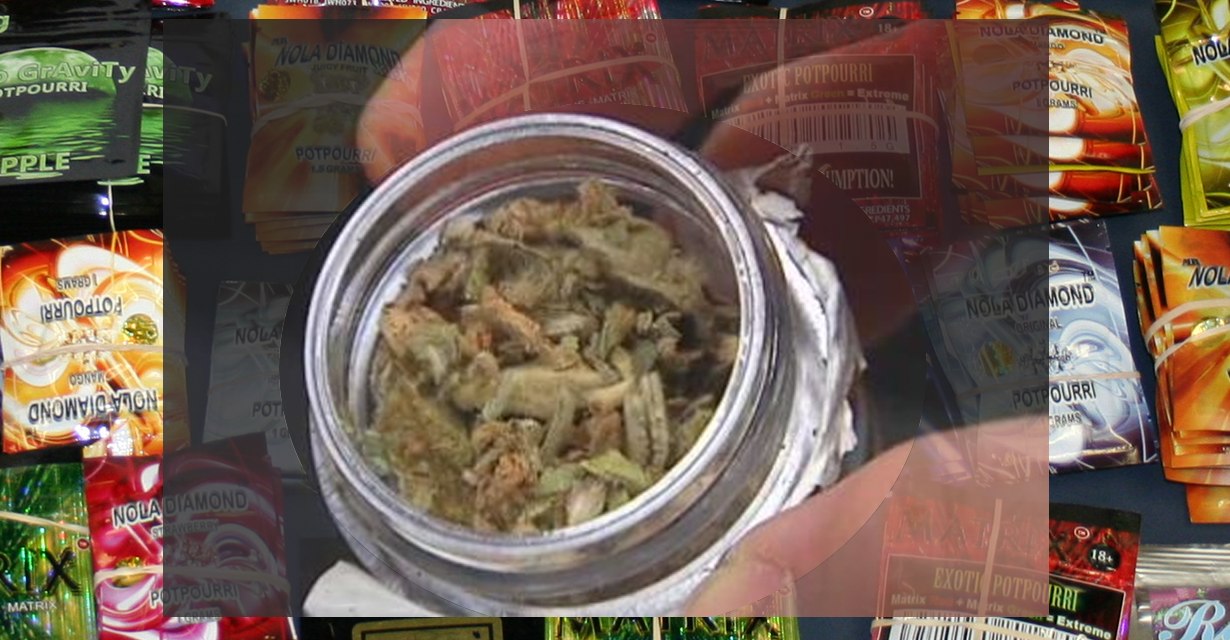

We’re seeing arguments for full legalization of all drugs, including old standards like heroin and cocaine as well as our newest worry, so-called ‘synthetic’ marijuana. Which is usually plant material sprayed with a THC-like chemical (there are a number). I saw one opinion piece urging us to legalize synthetics now so as to avoid the awful consequences of prohibition.

Legalization arguments ordinarily focus on regulation of the production and sale of potentially harmful drugs. This could be expected to produce significant new tax revenue for the government, a portion of which could be set aside for prevention and treatment. Legalization proposals usually involve inspection of production facilities, licensing of sales outlets, accurate lists of ingredients, and the addition of warning labels. It’s an attractive package for a revenue-hungry legislature.

But in practice, how well does it work?

Most people assume that legalization eliminates criminal activity entirely, but that’s not actually the case, particularly where those new taxes cause prices to vary widely from region to region. For instance, authorities tell us that smuggling tobacco (“buttlegging”) is often far more profitable than heroin or cocaine. A truckload of cigarettes will bring a much higher price in New York City than in Virginia, which motivates large-scale trafficking northward. Same thing happened in reverse in the late 80’s as NY crack dealers realized their product would earn a lot more in DC than at home. It’s just not that far down I-95. Heck, you could take Amtrak.

If a drug is suddenly legalized, what are the penalties for breaking the new law? They’re often fairly light, which makes smuggling safer for the smuggler. We could increase those penalties, but that puts us back into the enforcement dilemma.

If smuggling cigarettes and alcohol are actually bigger problems in some ways than heroin and cocaine trafficking, why aren’t we reading about this in the media? Your guess is as good as mine.

As far as funds for prevention and treatment, we can look to our experience with problem gambling. Most states where gaming is legal have turned out to be pretty stingy. Connecticut provides free outpatient treatment, which makes eminent sense from a public health standpoint, but nearby Maryland, which pulls in more than $800 million annually from its limited number of casinos, splits $2-4 million between education programs and an epidemiology research project at the University. Nothing directly for treatment, although an estimated 4-5% of that casino revenue comes from people with gambling problems.

Why the differences between nearby states? The political process, of course. It’s based in haggling between competing interests. Like sausage– better not to know how it gets made.

Do prices decrease following legalization? They do, which means more new users. Of course, prices could go up in future, during a budget shortfall. We’ll still see competition from the black market. In Arizona and New Mexico, for example, about half the cigarettes consumed are actually illicit in origin. You may not have known that; it doesn’t get much free pub.

Labeling ingredients is a good idea, though the folks who buy synthetics are not likely to be all that health-conscious. As for warning labels, Big Tobacco was happy to make that concession as it actually strengthened their argument when sued by smokers who got lung cancer. “We warned ’em– it’s right there on the package”.

I’ve come to the conclusion that legalization as it will inevitably be practiced in many states is basically a ‘lesser of two evils’ solution. It looks good mainly in comparison with the difficulties of enforcement.

What would really make a difference? Possibly governments who were less motivated by the prospect of new revenue and more genuinely concerned with the welfare of its citizens.