We’ve heard quite a bit about the role of fentanyl and carfentanil in escalating OD risk among heroin users. But not as much about their unexpected intrusion into the cocaine supply.

Cocaine is back again, first in the Northeast but increasingly in other parts of the country. Here’s one of our earlier pieces on the subject.

In Cleveland, the coke is often cut with fentanyl. The user doesn’t know that.

Sharp rise in African American opioid overdoses has Cleveland officials worried

Which brings up a question: Why would a dealer or distributor secretly add fentanyl to street cocaine, thereby risking the lives of his customers? Is he trying to kill them off? Doesn’t sound like good business practice, does it?

No, it doesn’t. In the long-term, it won’t be. And a dramatic increase in OD rates such as in Cleveland will quickly draw attention from law enforcement and the media. Which means exposure, and potentially trouble, for the dealer.

So why risk it? It’s a short term strategy. The thinking: you lose a few customers, but others are already in the pipeline. As one street captain explained it to me: “Get the money now. If you don’t take it, somebody else will. Give the customer what they want. You not their mother.”

That conversation took place around the time of the 2008 financial crash. I remember thinking that guy could have made a fortune on Wall Street prior to the collapse.

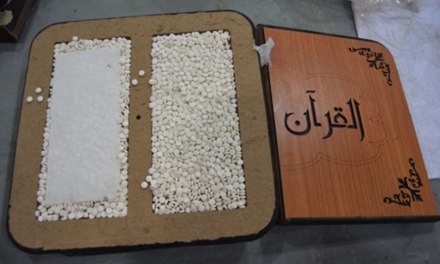

Cocaine has always commanded a relatively high price on the street. Nationally, I’m told, the average is in the neighborhood of $80-90 per gram. At that price point, an eighth of an ounce (“8-ball”) would sell for $280 to $315. So to extend the supply and further increase the profit margin, the product is often cut with a laxative or local anesthetic, or sometimes with an opioid to ‘smooth the ride.’

If you also sell heroin, you may already have fentanyl on hand. Even if you don’t, it’s available and cheap– in some areas, as little as $5.

Besides, you’re not going to tell the customer. Or in some cases, the seller. That’s the thing about illicit drug use– no quality control, no truth in advertising. The user just wants to get loaded. Or at least feel better, temporarily.

It’s about finding customers willing to risk it.

Which is not all that difficult. The rule on the street is caveat emptor, or “buyer beware”. But in this case, the purchaser may not be in any condition to exercise good judgment.