This New York Times opinion piece provides us with today’s topic.

What Republicans and Democrats Get Wrong About Crime

The author makes some interesting points about the way we treat criminals and crime in America.

First, though prisons will always be needed, we’ve relied too long on incarceration as our best hope for reducing crime. It hasn’t.

Second, it appears that the threat of long, punitive sentences hasn’t exactly put a stop to crime, either.

The real problem? The author argues it’s the arrest rate itself — the fact that only a relatively small percentage of those who commit crimes are arrested for them. Let alone tried and convicted.

And because the likelihood of being caught can be fairly remote, someone contemplating an offense likely knows in advance that the odds are in their favor.

So much for serving as a deterrent.

The author goes on to offer some familiar suggestions, all perfectly reasonable, ranging from increased funding, recruitment, and training for local police, to taking greater advantage of modern technology to improve the effectiveness of police work.

“Crime is not a partisan issue,” she reminds us, “and is too important for us to coast on stale ideas. Both sides need to put ideology aside and follow the evidence.”

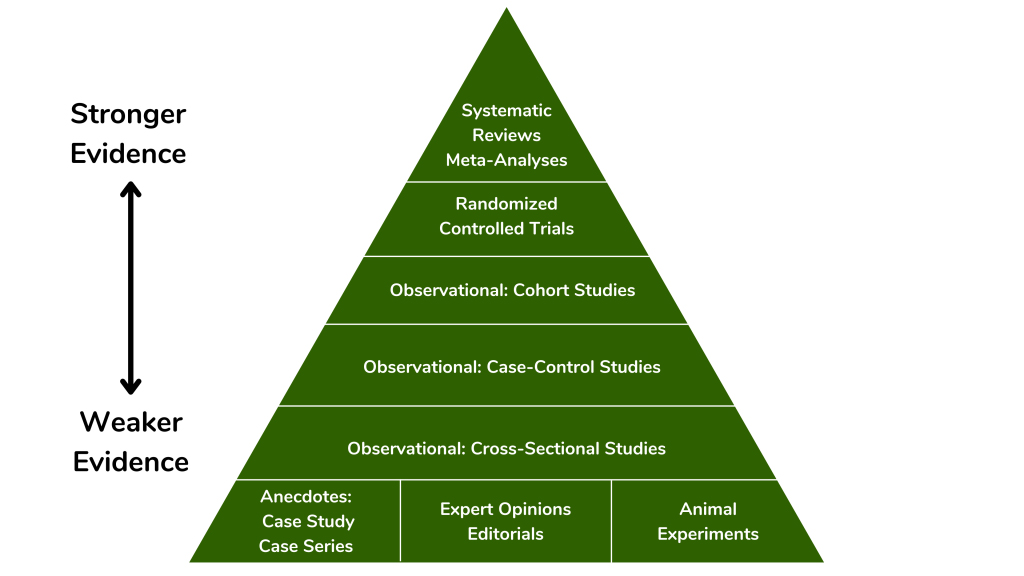

A worthy sentiment. By evidence, of course, she means good, solid, scientific evidence.

Science requires that valid evidence be obtained through methodologically sound research, using systematic observation and careful measurement, followed by critical review and evaluation. It’s that process, which takes time and money and planning, that makes scientific evidence as accurate and reliable as it is.

Unfortunately, that’s not the sort of evidence that sways the opinion of many voters. They rely on anecdotal evidence — meaning the type that is “…based on personal experiences, observations, or reports from individuals.” Anecdotal evidence may take the form of someone’s personal account or experience, and often, a story.

Stories, after all, are a great deal more accessible than science. And the reality is, only an estimated 25 to 30 percent of Americans are capable of reading and understanding the content of The New York Times Science section.

That isn’t enough to ensure a well-informed public around complex issues such as infectious disease, climate change, or criminal behavior. By the way, as disappointing as it may seem, 25-30% is nonetheless a big improvement over the 1980’s — before science instruction in schools was mandated and the science literacy scores began to climb.

When I was contemplating writing a book on juvenile justice, I decided to try using fiction instead of the usual nonfiction approach. I wound up writing a number of short stories based on my own and other people’s experience. I hoped that would better illustrate how the “system” actually works in practice — and sometimes, doesn’t work that well at all.

The fact is, it’s easier for most of us to relate to people than to populations. We care most about what happens to individuals and their families.

Did I guess right? I’m curious to find out.