Two announcements worth noting in recent weeks:

First up: following the lead of CVS and Walgreens, the Walmart corporation has proposed its own settlement with the 43 state and local governments currently suing the the company over its actions (and in some respects, inaction) during the prescription drug epidemic. Walmart’s pharmacy operation is smaller than CVS and Walgreens, so rather than the $5 billion agreed to by each of the others, Walmart is offering a reduced amount.

Walmart announces $3.1bn plan to settle opioids lawsuits

That’s a great deal of money, but in Walmart’s case, we’re talking about the world’s largest company by revenue — around $570 billion annually. According to PBS, the proposed settlement amount represents about 2% of their quarterly revenue.

In other words, they can afford it. I don’t see how we can expect corporations to avoid such risky behavior in future if it continues to pay off as well as prescribed opioids did. I mean, there’s the bad publicity that follows, sure. But that’s what all those PR firms exist to manage.

All three major corporate settlement agreements have yet to be completed, so we still have to wait to see where the money ultimately ends up, and to what extent it will have a positive impact on treatment and prevention in various areas of the country. That’s especially true given the size of the mess the legal system is now attempting to untangle. The prescription painkiller epidemic peaked around 2010, and here we are, twelve years later, wrangling over compensation.

By the way, Walmart took pains to let us know that despite agreeing to pay out billions in a settlement, they do not admit any liability. Per The Guardian, “Walmart… “strongly disputes” allegations… that its pharmacies improperly filled prescriptions for the powerful prescription painkillers.”

So in that respect, nothing’s changed. These prescriptions, they insist, were all authorized by licensed prescribers, qualified physicians and other professionals who bear all responsibility for the outcome. Certainly can’t blame the pharmacists who filled them. Or the corporate managers who allegedly advised pharmacists who questioned the practice to shut up and get back to pushing those pills.

Sigh.

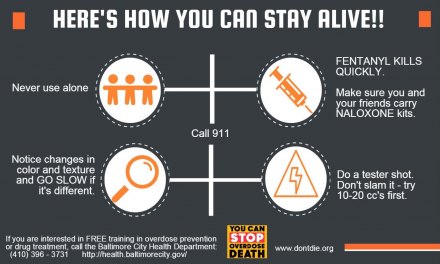

Moving on: It appears that the presence of other drugs in samples of fentanyl and heroin currently on our streets has made naloxone, the opioid antagonist that is our primary weapon against OD fatalities, less likely to be effective in the event of overdose. The FDA has sent round a letter notifying healthcare personnel of that altered reality.

In some cases, drugs sold as heroin or meth contain xylazine, an animal tranquilizer used in veterinary medicine for its sedative, muscle relaxant, and painkilling properties. Its street name is tranq.

I’d never heard of it, so I went hunting for something to compare. The closest I found was clonidine, the anti-hypertensive drug that was sometimes employed as a detox med, before the advent of buprenorphine.

Because xylazine is not an opioid, naloxone has no effect. The FDA warns that xylazine also may not show up on routine tox screens, so emergency personnel may have no way of recognizing its presence.

Sounds like yet another good reason to avoid using street drugs in the first place – as if we needed one.