The headline: “Did Americans Turn to Opioids Out of Despair – or Just Because They Were There?”

This article takes another look at the factors that drive the opioid epidemic, based on the work of Christopher Ruhm, who examines the thesis set forth by economics researchers Deaton and Case, who concluded that the rapid escalation of opioid use and related fatalities was a sign of a community in “despair” from an eroding social structure. Think job loss, declining wages, parental neglect, broken homes, etc. Ruhm tests these assumptions and concludes that although such factors may influence a drug epidemic, they’re not its primary cause. For that, he suggests, we should look once again at the supply side.

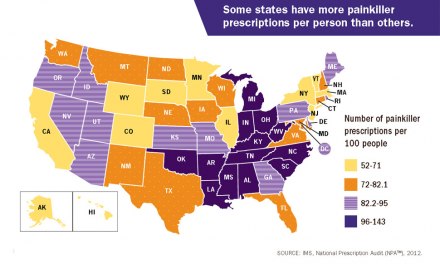

It makes sense: Drug epidemics depend on access to drugs, and without sufficient access, not enough people can get hold of the desired substances to foster an epidemic. With cocaine, for instance, the watershed event occurred when traffickers realized you could fit a whole lot more cocaine than marijuana in the hold of a smuggler’s small plane — therefore reaping far greater profits per shipment. At the time, cocaine was primarily a drug of the moneyed classes. The researcher Mark Gold referred it to as a “drug of disposable income” Whatever money you had, cocaine would help you dispose of it. From an economist’s perspective, these privileged folks represent the opposite of unemployed miners in Appalachia. And yet it was the rich folk who drove the epidemic in its early stages.

I suspect the popularity of Deaton and Case’s model reflects a preference in the academic world for certain types of social theories. A friend and lifelong Democrat, who’d served in the substance abuse administrations of three different states, once remarked that addiction treatment often did better under Republican administrations. “We Democrats always get stuck trying to cure poverty,” he groused. His argument: Once addicts got into recovery, they were invariably more successful in their lives. So why not focus our attention on that goal first?

That was his view. Of course, the current White House hasn’t focused on the drug problem, either. Things change, I guess.

With some caveats, I’d agree that when the supply is abundant, tjhe demand for drugs responds favorably. Drugs reinforce their own use. Addiction will be the outcome for a solid minority of those who at least experiment with the drug (well, except for tobacco). Not everyone who tries an addictive substance will develop an addictive disease. And a good thing it is, too.

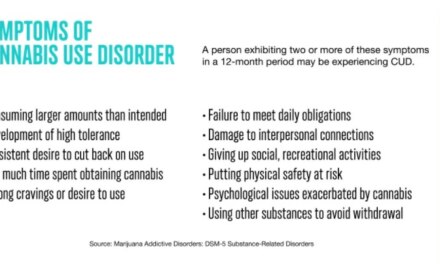

The second factor in the genesis of addiction is vulnerability. That’s partly genetic, part environmental. One person may progress into addiction quickly, another may get away with regular use for years before losing control. Some will become dependent on the drug but quit voluntarily — motivated by the fear of consequences. Unfortunately, we can’t predict in advance which user will fall into which category. And frankly, neither can they.

That’s why it’s so difficult to intervene early. By the time someone recognizes their own addiction, it’s deeply rooted in every aspect of life.

You might think of addiction in terms of hardware and software. Addictive drugs alter the brain– the hardware, so to speak– but the environment influences the expression of addiction in the individual — the “software”. And when someone goes to ‘unpeel’ this longstanding behavior, they wind up addressing both sides of the equation.

It occurs to me that despite all the debate about nature vs nurture, it’s always both. They vary in importance from person to person. But they’re always present in tandem.